Last updated on January 23rd, 2026 at 08:26 pm

Welcome to Tax Planning for Gen X and Retirees, this comprehensive guide will lay out for you the key elements you should consider when planning for your future weather you are a Gen X or already retired.

1. Tax Planning Is About Understanding the Rules — Not Cheating Them

Tax planning is not about gaming or cheating the system.

It is about understanding how the tax system is designed to work and arranging your financial decisions intelligently so that more of your retirement income works for you, rather than being lost to unnecessary taxes.

The U.S. tax code is intentional. It is structured to:

- Encourage certain behaviors

- Discourage others

- Allow taxpayers to legally minimize taxes through planning

This is precisely why tax planning for Gen X and retirees is not only legitimate—it is expected. Congress routinely uses the tax code to guide savings behavior, retirement preparation, homeownership, healthcare planning, and even where people choose to live.

- 1. Tax Planning Is About Understanding the Rules — Not Cheating Them

- 2. One Tax System, Two Very Different Planning Realities

- 3. Taxes Are Triggered by Events, Not Balances

- What Greg Could Have Done Differently

- What Greg Could Have Done Differently

- Side-by-Side Comparison: Greg’s Unplanned vs. Planned Approach (Updated)

- 4. The Tax Code Is Designed for Planning — Not Guesswork

- 5. Good Tax Planning Is Intentional — Not Reactive

- 6. Relocation Is a Legitimate — and Often Powerful — Tax Strategy

- 6A. Why Location Matters More in the Second Half of Life

- 6B. Gen X: Relocation Is a Long-Term Positioning Decision

- 6C. Retirees: Relocation Can Reduce Ongoing Tax Events

- 6D. The “Tax and Spend” Culture Question

- 6E. Relocation Is a Planning Tool — Not an Obligation

- 8B. Gen X: You Are Planning for a Moving Target

- 8C. Retirees: Stability Matters More Than Optimization

- 8D. Taxes Are Only One Part of the Equation

- Key Takeaway for This Section

- From Understanding to Action

- How to Use This Checklist

- Decision Checklist

- 10 Common Questions About Tax Planning for Gen X and Retirees

As Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes famously said:

“Tax avoidance is not a crime. Anyone may arrange his affairs so that his taxes shall be as low as possible.”

Photo: Library of Congress (Harris & Ewing collection).

There is, however, a clear and important line that must never be crossed.

You must never evade taxes you owe — that is a crime.

What you are absolutely allowed — and encouraged — to do is avoid unnecessary taxes legally.

Much of effective tax planning centers on understanding tax events—when income is actually taxed—rather than simply focusing on account balances. We explore this concept in more detail later in this guide and in related articles such as

<a href=”/tax-advantaged-retirement-accounts/” style=”font-weight:600;”>Tax-Advantaged Retirement Accounts</a>, which explains how different accounts interact with the tax system over time.

You also have choices.

You have the right to live wherever you choose.

You have the right to remain in a high-tax state such as California.

And you have the right to move to a lower-tax state if doing so improves your financial security and quality of life.

Where you live can directly affect:

- How retirement withdrawals are taxed

- Whether Social Security or pension income is taxed

- Property tax burdens

- Long-term cost of living

These issues are explored further in our relocation and state tax planning resources, including

State Income Tax Rates by State and Relocation as a Retirement Tax Strategy.In retirement, these choices matter more than ever because income often becomes fixed or semi-fixed, while taxes do not automatically decline unless you plan for them.

This article focuses on tax planning for Gen X and retirees, two groups facing very different realities:

- Generation X, roughly 20 years from retirement and still earning income, with time as their greatest planning advantage

- Retirees, generally age 65 and over, focused on managing withdrawals, controlling tax events, and preserving long-term financial stability

While their strategies differ, both groups benefit from learning how to adapt to the tax system rather than fight it.

That adaptive mindset—combined with informed decisions about income timing, withdrawals, and location—is the foundation of effective tax planning for Gen X and retirees.

This guide shows how Gen X and retirees can do exactly that, legally, strategically, and with confidence.

Want to compare retirement accounts that can help reduce taxes now or later? Use this guide to understand the most common tax-advantaged options and how they typically work.

Read the guide →2. One Tax System, Two Very Different Planning Realities

Tax planning does not happen in a vacuum.

It changes based on where you are in life, even though the tax system itself remains the same.

Rather than repeating definitions in text, this article uses the visual below to clearly distinguish between the two audiences this guide is written for:

- Generation X, still working and planning ahead

- Retirees, already managing withdrawals and tax events

The infographic that follows highlights why these two groups must approach tax planning differently—and why applying the wrong strategy at the wrong stage can be costly.

With that framework established, we can now move beyond who is planning and focus on how the tax system actually works.

3. Taxes Are Triggered by Events, Not Balances

The most important concept in tax planning is this:

You are taxed when a taxable event occurs — not simply because money exists.

A retirement account balance can sit there for years with no tax impact at all. But the moment you withdraw, sell, convert, or even change residency, you can trigger a taxable event. This is why effective tax planning is not just “saving money.” It’s learning how to control the timing and size of taxable events so you keep more of what you’ve earned.

Tax events most commonly come from:

- Earning income (W-2 or business income)

- Taking withdrawals from retirement accounts

- Selling appreciated assets

- Triggering residency/domicile rules in a new state

Once you understand that taxes are triggered by events, the planning goal becomes clear:

- Reduce the size of tax events

- Delay tax events when it benefits you

- Spread tax events across years (instead of stacking them)

- Avoid unnecessary penalties and bracket jumps

3A. Retirement Purchase Shock: The Retiree Car Example

This is how tax events surprise people in real life.

You are retired and decide to buy a new car. Rather than finance it, you withdraw $40,000 from your IRA and pay cash. Later, your CPA tells you that you owe tax on part of that withdrawal.

That was unexpected—because the prior year you could have withdrawn up to $20,000 and owed no federal income tax due to higher deductions.

The difference wasn’t the IRA.

The difference was the size and timing of the tax event.

✅ Lesson: Proper tax planning can reduce the pain of large purchases in retirement. Coordinating withdrawal timing, staging income across years, and planning around deductions can dramatically change the outcome.

A Gen X individual, age 55, earns $75,000 per year and decides to withdraw $150,000 from a traditional retirement account to purchase a home.

Because the withdrawal occurs before age 59½, it triggers both ordinary income taxes and a 10% early withdrawal penalty.

Step 1: Total Taxable Income

- W-2 income: $75,000

- IRA withdrawal: $150,000

- Total taxable income: $225,000

Step 2: How the $150,000 Withdrawal Is Taxed

| Bracket | Amount | Tax |

|---|---|---|

| 22% | $25,525 | $5,616 |

| 24% | $91,425 | $21,942 |

| 32% | $33,050 | $10,576 |

| Income tax on withdrawal | $150,000 | $38,134 |

Step 3: Early Withdrawal Penalty

Because the withdrawal occurred before age 59½:

- 10% penalty on $150,000 = $15,000

$38,134 income tax + $15,000 penalty = $53,134

Effective cost: ~35% of the withdrawal

Large, unplanned withdrawals can be extremely expensive. Early penalties combined with higher marginal tax brackets can dramatically reduce the amount of money you actually get to use. This is why Gen X tax planning focuses on avoiding unnecessary tax events and coordinating major purchases years in advance.

3B. Gen X Warning: Withdrawals Can Create Penalties and Bracket Shock

Gen X should generally avoid withdrawing funds from retirement accounts before age 59½ because early withdrawals often trigger a 10% penalty in addition to regular income taxes. That penalty becomes part of the tax event you must plan for.

Even when Gen X reaches an age where the penalty no longer applies, withdrawals while still working can cause a second problem: they can push income into higher tax brackets, increasing the marginal tax rate on the top portion of income.

In other words, the tax event isn’t just the withdrawal—it’s the withdrawal stacked on top of earned income.

3C. Case Study: Greg’s Down Payment Withdrawal at Age 55

Greg is a single 55-year-old Gen X professional earning $75,000 per year. He decides to buy a house and needs a down payment. Without checking the consequences, he withdraws $150,000 from his traditional retirement account and buys the house.

Greg didn’t do anything illegal.

He didn’t evade taxes.

He simply didn’t realize that this withdrawal would trigger multiple tax events at once.

Greg’s taxable income for the year

- Employment income: $75,000

- Retirement withdrawal: $150,000

- Total taxable income: $225,000

Because Greg is under 59½, his withdrawal triggers:

- Ordinary income tax (because it’s a taxable distribution), and

- A 10% early withdrawal penalty on the amount withdrawn

This is the “double hit” that catches many Gen X households off guard.

What Greg Could Have Done Differently

Greg’s mistake wasn’t buying a house.

It was making a single, irreversible tax decision without understanding the alternatives available to him.

With even modest planning, Greg had several options that could have dramatically reduced — or delayed — the tax damage.

Option 1: Borrow Instead of Withdraw (Up to $50,000)

Before touching his retirement account as taxable income, Greg could have explored borrowing from his employer-sponsored retirement plan.

Many plans allow participants to:

- Borrow up to $50,000 (or 50% of the vested balance, whichever is less)

- Avoid income taxes and the 10% early withdrawal penalty

- Repay the loan over time, typically through payroll deductions

- Pay interest to themselves, not a lender

This approach is not “free money” — the loan must be repaid, and failure to repay can convert the balance into a taxable distribution. However, it can be a powerful bridge strategy.

For Greg, borrowing $50,000 could have:

- Reduced his immediate cash need

- Lowered the taxable withdrawal required

- Kept him out of higher tax brackets

- Eliminated penalties on that portion entirely

Option 2: Reduce the Taxable Withdrawal Amount

Instead of withdrawing $150,000 all at once, Greg could have:

- Borrowed $50,000 from his plan

- Reduced the taxable withdrawal to $100,000

- Immediately avoided taxes and penalties on the borrowed portion

That single adjustment would have:

- Cut the early withdrawal penalty by $5,000

- Reduced the amount pushed into higher tax brackets

- Lowered total federal taxes due that year

Option 3: Spread Withdrawals Across Multiple Years

Greg could also have coordinated timing:

- Take smaller withdrawals over multiple tax years

- Keep annual taxable income below higher bracket thresholds

- Avoid stacking earned income and large withdrawals in the same year

Even without eliminating taxes, this strategy softens tax events rather than compounding them.

Option 4: Delay the Remaining Withdrawal Until Age 59½

By combining borrowing and staged withdrawals, Greg could have:

- Covered part of the down payment immediately

- Waited until age 59½ to withdraw the remaining funds

- Completely eliminate the 10% early withdrawal penalty on that portion

This is often the most powerful lever available to Gen X — time.

What Greg Could Have Done Differently

Greg’s mistake wasn’t buying the house. It was treating a retirement account like a cash account—without considering the tax consequences and alternatives.

Option: Borrow Up to $50,000 First (Then Plan the Rest)

Before creating a full taxable withdrawal, Greg could have explored a retirement plan loan (if his employer plan allowed it). Many plans allow borrowing up to $50,000 (or 50% of the vested balance, whichever is less). This can:

- Avoid the 10% early withdrawal penalty on the borrowed portion

- Avoid turning that portion into immediate taxable income

- Reduce the size of the tax event

- Allow Greg to withdraw the remaining need more strategically using the other planning suggestions (staging across years, delaying until 59½, partial financing, etc.)

This approach is not “free money”—it must be repaid, and plan terms matter.

Borrowing from a retirement plan can be useful in specific situations, but it is not appropriate for everyone and should never be treated as a default solution.

Borrowing is generally not advisable if:

- You are uncertain about job stability or expect a job change

- You may not be able to repay the loan on schedule

- Your plan requires immediate repayment upon job separation

- You are close to retirement and need the account fully invested

- You would be forced to default, turning the loan into a taxable distribution

If a retirement plan loan is not repaid as required, the outstanding balance can become a taxable distribution, potentially triggering income taxes and early withdrawal penalties.

Borrowing can reduce immediate tax pain when used carefully and temporarily, but it introduces repayment risk and should only be considered as part of a broader, well-thought-out tax plan.

3D. Planned vs. Unplanned: Why Strategy Matters

A good way to understand tax planning is to compare two paths:

- Unplanned: one large withdrawal, one large tax event, penalty + bracket pressure

- Planned: borrow what you can (if appropriate), reduce the taxable withdrawal, spread it across years, and time withdrawals to avoid unnecessary penalties and thresholds

Side-by-Side Comparison: Greg’s Unplanned vs. Planned Approach (Updated)

| Decision Area | Unplanned Withdrawal | Planned Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Age at withdrawal | 55 | 55–59½ |

| Cash needed | $150,000 | $150,000 |

| Borrowed from plan | $0 | $50,000 |

| Taxable withdrawal | $150,000 | $100,000 (initially) |

| Early withdrawal penalty | $15,000 | $10,000 → $0 later |

| Highest tax bracket hit | 32% | Likely 24% |

| Flexibility | None | High |

| Ability to adjust later | No | Yes |

3E. Use the Interactive Decision Tool

When you need cash for a major purchase, there are usually multiple ways to fund it—and only some of them are tax-efficient.

To help readers think clearly before acting, we created a simple decision tool:

“Should You Withdraw, Borrow, or Wait?”

Should You Withdraw, Borrow, or Wait?

Use this quick tool to see which path may be less painful tax-wise when you need cash for a major purchase. (Educational guidance only—rules and plan terms vary.)

3F. Deeper Account Mechanics

This article focuses on tax strategy and tax events, not the mechanics of every account type. If readers want the full breakdown of how retirement accounts and HSAs work in practice—including the deeper HSA strategy—send them here:

- /tax-advantaged-retirement-accounts/ (insert your button CTA)

4. The Tax Code Is Designed for Planning — Not Guesswork

One of the most common mistakes people make is assuming the tax system is fixed and unavoidable. It isn’t.

The federal tax code is intentionally structured to reward planning and punish improvisation. Congress uses taxes to shape behavior—how people save, when they retire, how they withdraw money, and even where they choose to live.

That design reality matters for both Gen X and retirees.

Major tax changes enacted in 2017 and later extended and enhanced by subsequent legislation reshaped the way individuals are taxed. These changes did not eliminate taxes, but they shifted where planning opportunities exist. The biggest advantages today come not from aggressive deductions, but from controlling income, timing, and tax events.

For many households, the era of relying on large itemized deductions is over. In its place is a system that favors:

- Strategic income timing

- Coordinated withdrawals

- Awareness of thresholds and phaseouts

- Geographic flexibility

This is why two people with the same income can have dramatically different tax outcomes depending on how and whenthat income is recognized.

4A. Why Guessing Is Expensive

Tax surprises almost always come from guessing rather than planning.

People assume:

- A withdrawal will “probably be fine”

- A purchase won’t affect their taxes much

- A move won’t change anything materially

Then the tax return arrives.

As you’ve already seen in the examples earlier, large one-time actions—withdrawals, purchases, or moves—can stack on top of each other and create unexpected tax spikes. The tax code does not warn you in advance. It simply applies the rules after the fact.

Planning flips that dynamic.

4B. Gen X: Time Is a Planning Asset, But Only If You Use It

For Gen X, the tax code offers one powerful advantage: time.

Time allows:

- Income to be shifted across years

- Withdrawals to be delayed until penalties disappear

- Large decisions to be staged instead of stacked

But time only helps if it’s used intentionally. Waiting without planning is not a strategy—it’s just procrastination.

Gen X households that understand how tax brackets, penalties, and thresholds work can avoid the kinds of mistakes shown in Greg’s case study. Those who don’t often discover the cost years later, when options are limited.

4C. Retirees: Control Matters More Than Growth

For retirees, the planning challenge changes.

The focus is no longer on maximizing accumulation. It’s on controlling tax events year by year so withdrawals do not:

- Push income into higher brackets

- Increase taxes on Social Security

- Trigger higher Medicare premiums

- Create unnecessary state tax exposure

The tax code gives retirees more control than many realize—but only if withdrawals, purchases, and residency decisions are coordinated.

4D. Planning Windows Open and Close

Tax laws are not static. Deductions, thresholds, and credits can change, and some provisions include sunset clauses that automatically expire.

This creates planning windows—periods where certain strategies work especially well. Missing those windows often means waiting years for another opportunity.

The lesson is simple:

- Planning beats guessing

- Timing beats urgency

- Strategy beats reaction

Section 3 showed what happens when tax events are ignored.

Section 4 explains why the system behaves that way.

The sections that follow focus on how to use that reality to your advantage.

The Same Tax Code — Very Different Planning Rules

Gen X and retirees face different risks and opportunities under the same tax system. Planning succeeds when strategy matches life stage.

🟩 Gen X (≈20 Years from Retirement)

- Still earning W-2 or business income

- Paying income taxes at peak rates

- Greatest advantage is time

- Can delay withdrawals to avoid penalties

- Can spread large decisions across years

- Can plan *where* retirement income will be taxed

Position future withdrawals so taxes are paid later, at lower rates, and without penalties.

Large, unplanned withdrawals while still working can trigger penalties and higher tax brackets.

🟦 Retirees (Age 65+)

- Living on Social Security and withdrawals

- Income often fixed or declining

- Greatest advantage is control

- Can manage annual withdrawal amounts

- Can coordinate income with deductions

- Can relocate to reduce or eliminate state taxes

Control tax events year-by-year to avoid income spikes, penalties, and hidden thresholds.

One-time purchases or large withdrawals can unexpectedly increase taxes and costs.

Gen X uses time to reduce future taxes. Retirees use control to manage current tax events. The tax code rewards both — but only when planning replaces guesswork.

5. Good Tax Planning Is Intentional — Not Reactive

By this point, one theme should be clear:

tax problems rarely come from high income alone. They come from unplanned decisions.

Most people do not wake up intending to trigger penalties, jump tax brackets, or create unnecessary tax bills. Those outcomes usually happen because a financial decision is made first — and the tax consequences are discovered later.

Good tax planning flips that order.

Instead of asking “What will this cost me in taxes?” after the fact, effective planning asks:

- What tax event does this decision create?

- Can that event be delayed, reduced, or spread out?

- Is there a lower-tax way to accomplish the same goal?

This mindset applies equally to Gen X and retirees, even though the tactics differ.

5A. Planning Is About Sequencing Decisions

Taxes care deeply about sequence.

When income, withdrawals, purchases, and moves happen in the wrong order, they stack on top of each other. That stacking is what creates:

- Penalties

- Bracket jumps

- Lost deductions

- Higher lifetime tax costs

When decisions are sequenced intentionally, many of those outcomes can be softened or avoided.

Greg’s case study illustrated this perfectly. The issue wasn’t the house. It was the order in which Greg accessed his money.

5B. Gen X: Use Time to Control Future Tax Events

For Gen X, planning is primarily about positioning.

Time allows Gen X to:

- Delay withdrawals until penalties disappear

- Spread large needs across multiple years

- Avoid stacking earned income and withdrawals

- Decide where retirement income will ultimately be taxed

But time only works if it is used deliberately. Waiting without a plan simply defers the problem.

Gen X households that think ahead can avoid becoming future examples like Greg. Those that don’t often discover the cost later, when flexibility is gone.

5C. Retirees: Control Is More Valuable Than Growth

For retirees, the planning advantage shifts from time to control.

In retirement, you often control:

- When income is recognized

- How much income is recognized each year

- Which sources of income are tapped first

- Where that income is taxed

This is why retirees with similar net worths can have wildly different tax outcomes. The difference is rarely the account balance — it is withdrawal strategy and timing.

Large, reactive withdrawals tend to create tax spikes. Smaller, coordinated withdrawals tend to create stability.

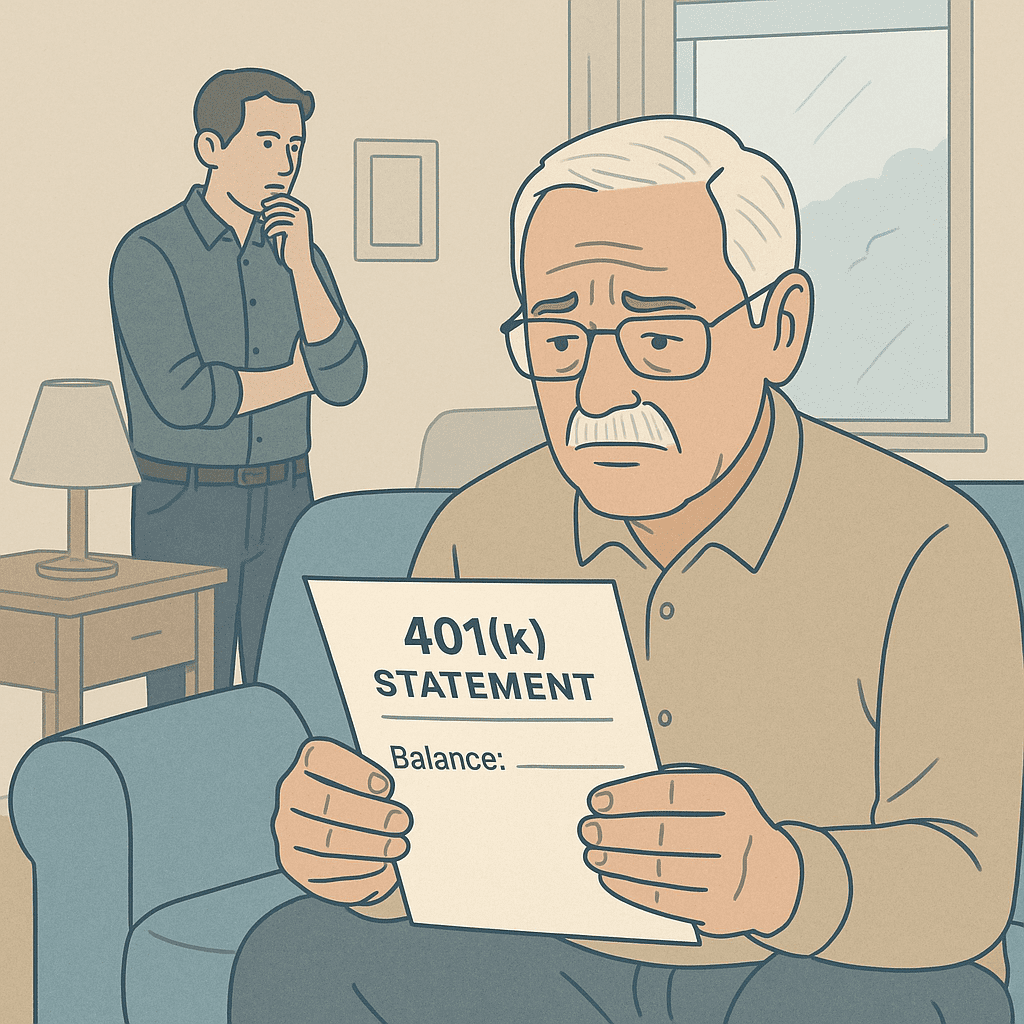

Tax-advantaged retirement accounts were designed for retirement — not as a piggy bank.

Before removing funds early, it’s worth asking a hard question:

What will future you say when reviewing a 401(k) or IRA statement and finding that it holds only half of what is needed for a comfortable retirement?

Will future you wish that Gen X you had exercised more restraint? That you had explored other options before turning long-term retirement savings into short-term spending money?

The taxes and penalties from early withdrawals are visible immediately. The opportunity cost — what that money could have grown into — often isn’t felt until it’s too late to fix.

5D. Planning Means Looking Ahead — Not Just This Year

One of the biggest mistakes in tax planning is thinking one year at a time.

Taxes are cumulative.

Decisions made at 55 affect outcomes at 65.

Decisions made at 65 affect outcomes at 75.

Effective planning looks forward:

- Across multiple tax years

- Across life stages

- Across potential changes in income and location

This is especially important given that tax laws change and some provisions expire. Planning windows open and close, and the people who benefit are usually the ones already prepared.

5E. Strategy Beats Sophistication

You do not need complex structures or exotic strategies to plan well.

What you need is:

- Awareness of tax events

- Willingness to slow down major decisions

- Understanding that most financial goals have multiple funding paths

The tax code does not reward speed.

It rewards intentionality.

6. Relocation Is a Legitimate — and Often Powerful — Tax Strategy

Relocation is one of the most misunderstood areas of tax planning.

For some reason, changing where you live is often treated as an emotional or political decision rather than what it frequently is: a financial decision with long-term tax consequences.

The reality is simple:

- You have the right to live in a high-tax state

- You have the right to stay there for personal, family, or career reasons

- And you also have the right to move if doing so improves your financial security

None of those choices are wrong. But pretending they are tax-neutral is a mistake.

6A. Why Location Matters More in the Second Half of Life

Early in your career, high state taxes can be partially masked by rising income, promotions, and employer benefits. Later in life, those same taxes become more visible — and more permanent.

As income shifts from:

- Earned wages → retirement income

- Growth → withdrawals

- Accumulation → preservation

The ongoing tax drag of where you live matters more than ever.

For retirees especially, state tax policy directly affects:

- IRA and 401(k) withdrawals

- Pension income

- Social Security taxation

- Property taxes

- Sales and excise taxes

Once you are no longer offsetting taxes with growing income, location becomes a controllable variable — if you choose to use it.

6B. Gen X: Relocation Is a Long-Term Positioning Decision

For Gen X, relocation planning is rarely about moving tomorrow. It’s about positioning future income.

Questions worth asking now:

- Where will my retirement income be taxed?

- Will my state tax withdrawals, pensions, or Social Security?

- Will high property taxes follow me into retirement?

- Do current policies suggest future increases?

Relocation planning for Gen X is less about packing boxes and more about keeping options open. Knowing where you could retire allows better decisions about where and how to save today.

6C. Retirees: Relocation Can Reduce Ongoing Tax Events

For retirees, relocation is often the most direct way to reduce taxes without changing spending or lifestyle dramatically.

Moving from a high-tax state to a lower-tax one can:

- Reduce or eliminate state income tax on retirement income

- Lower property tax burdens

- Reduce sales and excise taxes

- Simplify withdrawal planning

Importantly, this isn’t about avoiding taxes altogether. It’s about avoiding unnecessary taxes that continue year after year.

A one-time move can permanently change your tax environment.

6D. The “Tax and Spend” Culture Question

Taxes do not exist in isolation. They reflect policy choices.

Some states and localities rely heavily on:

- High income taxes

- High property taxes

- Layered local taxes

Others rely more on:

- Consumption taxes

- Broader tax bases

- Lower rates across more people

Neither approach is inherently right or wrong. But they produce very different outcomes for retirees and near-retirees.

When evaluating relocation, it’s reasonable to ask:

- Does this area have a history of raising taxes?

- Are retirement incomes protected or targeted?

- Are property taxes predictable or volatile?

Past behavior is often the best indicator of future policy.

6E. Relocation Is a Planning Tool — Not an Obligation

Relocation is not required to plan well.

Many people will stay exactly where they are and plan successfully using withdrawal timing, account sequencing, and careful spending.

But for others, relocation becomes the single biggest tax decision they ever make — not because it’s dramatic, but because it quietly reduces taxes every year thereafter.

The key is choice.

Tax planning works best when you recognize which variables you can control:

- Timing

- Amounts

- Sequence

- Location

Sections 3–5 focused on timing and sequence.

Section 6 introduces location as another lever — one that is often overlooked, but powerful when used intentionally.

Relocation can dramatically change your retirement math — often more than any single investment decision.

Before dismissing relocation as “not for you,” we strongly encourage reading our in-depth guide on selecting where to relocate. The article includes an embedded decision tool that helps you evaluate costs, taxes, and lifestyle tradeoffs.

In some regions — even within the same state — retirees can live comfortably on 40% or more less income due to lower housing costs, reduced taxes, and fewer recurring expenses.

Read the article before deciding whether staying put is truly the best option.

Available on Apple Podcasts and most major podcast platforms.

- Reduced state income tax on earned income

- Publicly discussed the goal of eliminating earned income tax altogether

That trend tells you something about future policy risk.

By contrast, some high-tax states have a long history of:

- Adding surcharges

- Narrowing deductions

- Expanding taxable income categories

- Increasing local and special-district taxes

History is often the best predictor of future behavior.

8B. Gen X: You Are Planning for a Moving Target

For Gen X, the danger is assuming today’s tax rules will still exist when you retire.

You are planning for:

- 10, 15, or 20 years into the future

- A different political and economic environment

- Different budget pressures at the state and local level

That makes flexibility critical.

Good Gen X tax planning means:

- Keeping multiple relocation options viable

- Avoiding irreversible decisions too early

- Understanding which states are becoming more — or less — retirement-friendly over time

You are not choosing a state today.

You are choosing options.

8C. Retirees: Stability Matters More Than Optimization

For retirees, the focus shifts from optimization to stability.

A state with predictable, restrained tax policy often beats a state that offers:

- Temporary exemptions

- Complicated carveouts

- Income-based phaseouts

Stability reduces:

- Surprise tax bills

- Forced lifestyle adjustments

- Stress around withdrawals and budgeting

The goal is not perfection.

The goal is confidence.

8D. Taxes Are Only One Part of the Equation

A low-tax state is not automatically a good retirement state.

You still need to weigh:

- Healthcare access

- Insurance costs

- Housing availability

- Climate and disaster risk

- Community and lifestyle fit

Tax planning works best when it supports the life you want — not when it drives every decision.

Key Takeaway for This Section

The smartest tax planning decisions look beyond this year’s tax rate.

They consider:

- Policy direction

- Political culture

- Long-term sustainability

- How easy it is to adjust if conditions change

You don’t need to predict the future perfectly.

You just need to avoid ignoring it.

From Understanding to Action

By now, the picture should be clearer.

Tax planning is not about finding a perfect state, a perfect deduction, or a permanent solution that never changes.

It’s about direction, flexibility, and reducing avoidable surprises over time.

For Gen X, that means thinking ahead—sometimes decades ahead—while protecting future options.

For retirees, it means creating stability so withdrawals, budgets, and lifestyle choices don’t get disrupted by unexpected tax events.

Understanding these concepts is important.

Applying them to your own situation is where the real value begins.

The checklist below is designed to help you slow down, ask the right questions, and identify the next smart step—whether that’s learning more, modeling scenarios, or simply confirming that your current plan still makes sense.

There are no trick answers.

There is only clarity.

How to Use This Checklist

This checklist is not a test and it is not meant to be completed all at once.

Work through it at your own pace.

Check off what you already understand.

Leave the rest unchecked — those are your opportunities to learn, model, or revisit later.

For Gen X, this is about protecting future flexibility.

For retirees, it’s about reducing uncertainty and avoiding unnecessary tax friction.

Decision Checklist

Click to check items off. Your selections are saved on this device. Educational only — not tax or legal advice.

1) Where will my retirement income come from?

2) Does my state tax any of that income?

3) Am I looking at today’s taxes — or the trend?

4) Have I evaluated the full tax picture?

5) Gen X only — protecting “future you”

6) Retirees only — managing withdrawals intentionally

7) What is my next smart step?

10 Common Questions About Tax Planning for Gen X and Retirees

1) What does “tax planning for Gen X and retirees” actually mean?

2) Why does tax planning differ between Gen X and retirees?

3) What types of retirement income can be taxed?

4) Is tax avoidance legal?

5) Should relocation be part of tax planning?

6) Why are early retirement account withdrawals risky for Gen X?

7) How do withdrawals affect tax brackets in retirement?

8) Are zero-tax retirement states always better?

9) How often should tax plans be revisited?

10) What is the most important first step?

Disclaimer: This content is for educational purposes only and is not tax, legal, or financial advice. Consult a qualified professional regarding your specific situation.

Discover more from RetireCoast.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.