Here’s a short audio introduction to this article and why the stories behind America’s fight for independence still matter as we approach the 250th Anniversary. When you finish, explore more history in our America’s 250th Anniversary Hub .

Tip: If the audio player looks narrow on mobile, it will expand to full width inside this callout.

Introduction

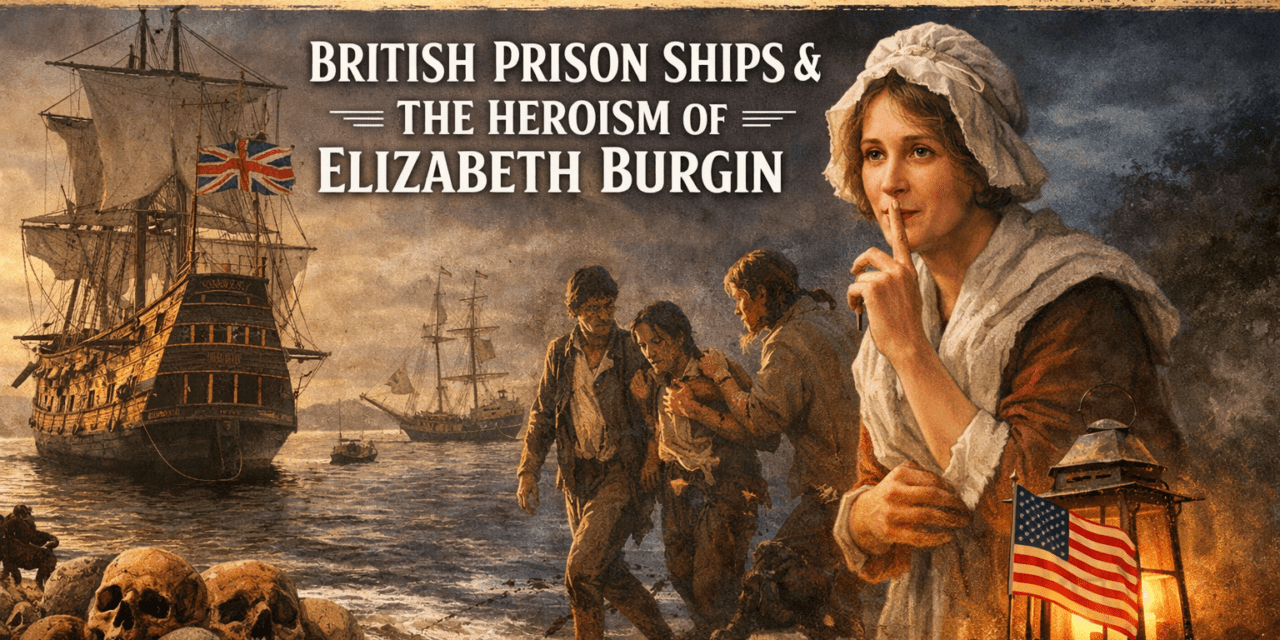

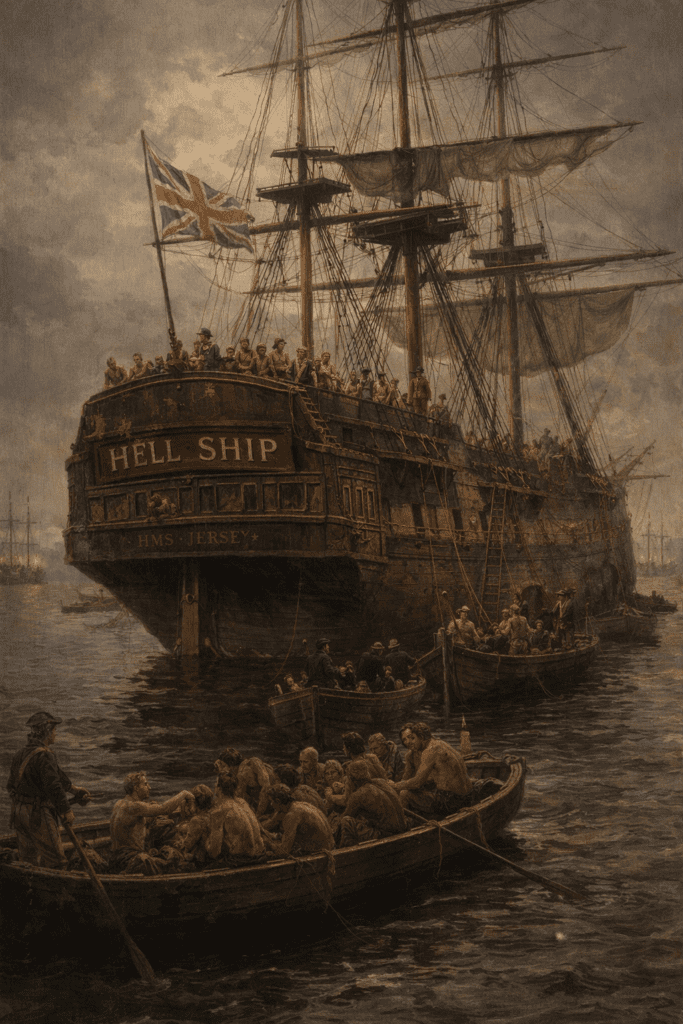

As the United States approaches the 250th anniversary of American independence, the story of the Revolutionary War is often told through famous battles, celebrated generals, and the signing of historic documents. Yet one of the deadliest and most consequential struggles of the war unfolded far from the battlefield—aboard British prison ships anchored in New York Harbor, just off the shores of Long Island, in the foul waters of the East River at Wallabout Bay.

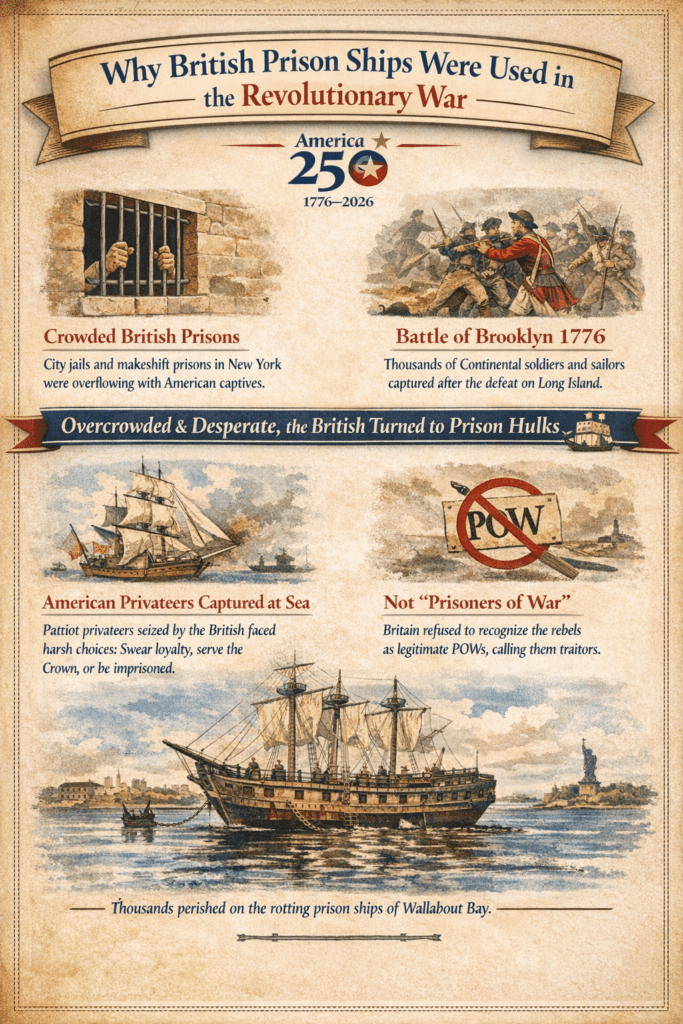

Following the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776 and the British occupation of New York City, the British army and British authorities found themselves holding large numbers of American prisoners—soldiers, sailors, privateers, and private citizens captured in the early years of the Revolutionary War. Lacking sufficient land-based prisons and unwilling to recognize the captives as legitimate prisoners of war, the British government turned to a grim solution already familiar in the 18th century: the use of prison hulks.

Aging British vessels, stripped of their guns and rigging, were repurposed as floating jails. What was intended as a temporary measure became one of the most lethal detention systems in the history of the war.

Aboard ships such as the infamous HMS Jersey, later remembered as the Old Jersey Prison Ship, thousands of men endured starvation, disease, contaminated water, and the near-total absence of medical attention.

- Introduction

- The Death Rate

- The Road to New York: Why British Prison Ships Became “Necessary”

- Wallabout Bay and the Making of a Floating Prison System

- A temporary measure

- Life Aboard the HMS Jersey: Survivor Testimony from the Old Jersey Prison Ship

- British Policy, Prison Hulks, and the Machinery of Captivity

- 1. The Hulks Act of 1776 (British Parliament)

- 2. British Naval & Commissary Correspondence (1776–1783)

- 3. British Justification: “Rebels,” Not POWs

- 4. The HMS Jersey and British Administrative Records

- Exchange, Endurance, and the Long Road to Freedom

- From Prison Hulks to Principles: What the Prison Ships Taught a New Nation

- Conclusion: Remembering the Prison Ships at America’s 250th Anniversary

The Death Rate

The death rate on these ships was staggering. More Americans died on British prison ships than were killed in combat during the entire war. Their bodies were buried in shallow graves along the Brooklyn shoreline, many of them nameless, their families never knowing their fate.

Yet even in this darkest chapter, resistance endured. While some prisoners were pressured to swear an oath of allegiance or enter British service, others refused under overwhelming odds.

A few escaped—often with help from courageous civilians. Among them was Elizabeth Burgin, a patriot woman who risked her life to aid the escape of American prisoners from British prison ships, a story highlighted in RetireCoast’s Women of the Revolutionary War series.

Her actions remind us that the fight for independence was waged not only by armies and navies, but by ordinary individuals willing to defy British rule in extraordinary ways.

This article is part of RetireCoast’s America’s 250th Anniversary Hub Pages 250th Anniversary series, which seeks to revisit the Revolutionary era not as myth, but as lived experience. By examining the British prison ships of Wallabout Bay—how they operated, who suffered aboard them, and why their legacy still matters—we honor the

Prison Ship Martyrs and confront a truth essential to understanding American independence: liberty was not only won on the battlefield, but survived in places where hope itself was nearly extinguished.

As part of RetireCoast’s America’s 250th Anniversary series, this short reading features George Washington protesting the treatment of American prisoners held aboard British prison ships in New York Harbor. Washington also warns that prisoner treatment works both ways — a reminder of the era’s expectations for reciprocal conduct during wartime captivity.

Attribution: George Washington, letter concerning the conditions of American prisoners on British prison ships, dated January 13, 1777 (as published in the National Archives’ Founders Online). Audio reading produced for RetireCoast.

The Road to New York: Why British Prison Ships Became “Necessary”

In the early years of the Revolutionary War, the struggle for American independence was not fought solely with muskets and cannon. It was also fought through captivity—through who would be held, how they would be treated, and whether their suffering might pressure the Continental Congress and the Continental government to bend.

After the fighting shifted from Boston Harbor to the middle colonies, George Washington understood that the next decisive contest would center on New York City and control of its waterways.

Following the British evacuation of Boston in March 1776, Washington moved the Continental Army toward New York. The stakes were obvious. The city’s deep harbor and the Hudson River formed a strategic corridor that could divide the American colonies in half.

When General William Howe and British forces landed on Long Island in August, the Battle of Brooklyn—also known as the Battle of Long Island—proved disastrous for the Americans. Although Washington’s nighttime withdrawal from Brooklyn Heights saved thousands of his men, the British army soon secured firm control of New York City, which it would hold until the end of the war.

British Controlled Manhattan

British control of Manhattan created a second, immediate problem: prisoners. In rapid succession, British soldiers and British officers captured or arrested large numbers of Americans. These included Continental troops taken after engagements around New York, private citizens accused of disloyalty, and especially American sailors seized at sea.

Although the Continental Navy was small, the Continental government authorized private enterprise to fight on behalf of the patriotic cause. American privateers and other armed ships harassed British commerce, and when British authorities captured those American ships, their crews faced grim choices.

They could swear an oath of allegiance, enter British service aboard Royal Navy vessels, or endure confinement as enemy prisoners.

The infographic below traces how thousands of captured Americans ended up aboard British prison ships, revealing how geography, policy, and war combined to make Wallabout Bay one of the deadliest places of the Revolution.

At the same time, the British crown refused—particularly in the early stages of the conflict—to recognize many captives as conventional prisoners of war. British rule depended on maintaining the claim that the rebellion was an internal affair, involving rebels rather than a legitimate opposing nation. While formal executions were largely avoided, neglect often achieved the same end.

Disease, starvation, and bad water could quietly accomplish what the gallows would do publicly. It was this reality that made Washington’s protests over the treatment of prisoners so urgent. His warnings about reciprocal treatment reflected a growing concern that captivity itself was becoming a deliberate instrument of war.

Jails and Warehouses were never designed as prisons

On land, New York’s existing British prisons and improvised detention sites—jails, warehouses, churches, and other buildings—were never designed to hold the flood of captives pouring in during 1776 and 1777. With the city already strained by wartime disruption and overcrowding, British forces began looking beyond the shoreline for solutions.

That search would soon lead them to the anchored hulks in Wallabout Bay.

Wallabout Bay and the Making of a Floating Prison System

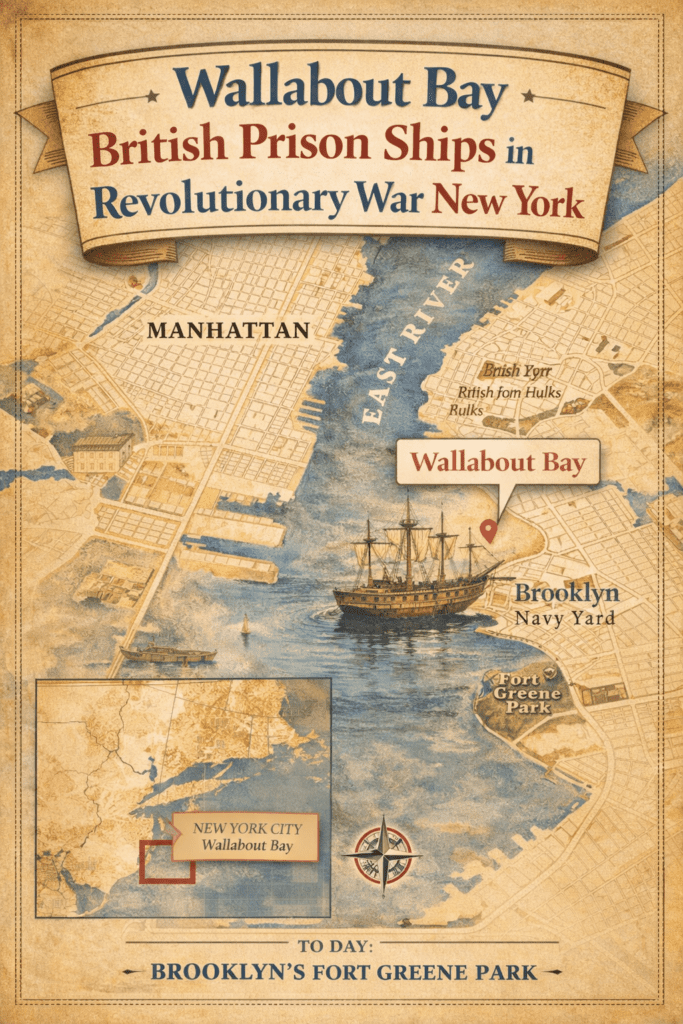

Once British authorities accepted that land-based confinement in New York City was insufficient, geography offered a grim solution. Wallabout Bay, a shallow, sheltered inlet along the East River on the northwestern edge of Brooklyn, lay just beyond the city’s crowded streets yet remained firmly under British control.

The bay sat opposite Manhattan, near what would later become the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and was easily guarded by British warships and shore patrols. It was close enough to supply, distant enough to isolate, and invisible enough to allow suffering to unfold largely out of public view.

British Ships were anchored in the bay

By late 1776, British vessels no longer fit for combat were anchored in the bay and converted into prison hulks. These were not purpose-built detention facilities. They were aging transport ships, former Royal Navy vessels, and captured American ships, stripped of rigging, guns, and fittings.

Their dark holds—designed to carry cargo or livestock—were now packed with human beings. The first prison ship anchored in the Wallabout was the Whitby, followed by others such as the Good Hope, Falmouth, and, eventually, the most infamous of all, the HMS Jersey, remembered by survivors as the Old Jersey Prison Ship.

A temporary measure

The British described this arrangement as a temporary measure, but the scale of the war quickly made it permanent. After the capture of Fort Washington and continued fighting around New York and Long Island, prisoners arrived faster than exchanges could be arranged. American sailors, American privateers,

Continental soldiers, and even private citizens accused of aiding the rebellion, were confined together. Many were denied recognition as legitimate prisoners of war, a policy rooted in the British crown’s refusal to acknowledge the sovereignty of the United States during the early years of the conflict.

Conditions aboard the prison ships were catastrophic. Prisoners were crowded below decks with little ventilation, forced to drink bad water, and given inadequate rations. Medical attention was virtually nonexistent, even as diseases such as yellow fever, typhus, dysentery, and smallpox spread rapidly.

The death rate aboard some ships climbed into double digits per day. Bodies were removed each morning and buried in shallow graves along the Brooklyn shoreline, where tides and storms often exposed them again.

Prison ships, a “logical necessity.”

Despite these conditions, British officers continued to present the prison ships as a logistical necessity rather than a moral failing. Yet even at the time, their use was controversial. George Washington, members of the

Continental Congress and other American leaders protested the treatment of prisoners and warned that cruelty would invite reciprocal treatment of British prisoners of war.

Those warnings went largely unheeded. By the time of the British surrender at Yorktown and the end of the war, more Americans had died aboard prison ships in Wallabout Bay than had fallen in combat during the entire Revolutionary War.

For the men held there, Wallabout Bay was not merely a place on a map. It became a symbol of captivity, neglect, and endurance—a reminder that the fight for independence was waged not only on battlefields, but in the dark, airless holds of ships where survival itself became an act of resistance.

Life Aboard the HMS Jersey: Survivor Testimony from the Old Jersey Prison Ship

Among the many British prison ships anchored in Wallabout Bay, none became more feared—or more deadly—than the HMS Jersey. Originally a sixty-four-gun warship, the Jersey had been stripped of her armament, rigging, and fittings and repurposed into a floating prison.

Rudderless and permanently moored in the East River, she loomed just offshore, visible from Brooklyn yet unreachable to those trapped inside. To the thousands of American prisoners confined within her rotting hull, she was not simply a ship, but a sentence.

Survivors consistently described conditions aboard the Jersey as worse than any battlefield hardship. Prisoners were packed tightly below decks in near darkness, where ventilation was almost nonexistent. The heat in summer was suffocating; in winter, bitter cold settled into the damp timbers.

Water was polluted

Food was scarce and often inedible. Water, drawn from polluted sources, was foul-smelling and unsafe to drink. Medical care was virtually nonexistent, even as disease swept through the ship.

Poet and privateer Philip Freneau, who spent weeks aboard British prison ships in 1780, left one of the most vivid accounts. In his poem The British Prison Ship, he described men “fainting through the day,” confined in “these damn’d hulks,” where starvation and sickness claimed lives daily.

Freneau later wrote that the stench below decks was so overpowering that breathing itself became a struggle, and that death was often greeted not with fear, but with resignation.

Captain Thomas Dring, another survivor of the Jersey, recalled that the cook—ironically—was often the healthiest man aboard, not because conditions were better for him, but because he alone had regular access to food.

Around him, prisoners wasted away into what Dring described as “living skeletons,” their strength consumed by hunger and disease. Dysentery, typhoid, smallpox, and yellow fever spread unchecked, turning the ship into what many later called a floating pesthouse.

The dead were buried on the beach

Each morning, the dead were brought up from below decks. Bodies were stacked on planks and ferried ashore to be buried in shallow graves along the Brooklyn shoreline.

Some corpses went undiscovered for days, hidden in the darkness below, their presence revealed only by the smell. No proper records were kept. Most of the dead were never identified. For families across the American colonies, loved ones simply vanished.

British officers occasionally offered prisoners a way out: enlistment in British service aboard Royal Navy vessels, or an oath of allegiance to the Crown. Some accepted, driven by desperation. Many refused. As

Ethan Allen, himself a former prisoner, later wrote, hundreds chose death rather than fight against their own cause. For those who remained, survival depended on endurance, luck, and—on rare occasions—escape.

“Many hundreds, I am confident, submitted to death, rather than to enlist in the British service.”

Ethan Allen, captured after the capture of Fort Ticonderoga and later imprisoned by British authorities, wrote these words after witnessing the conditions faced by American prisoners of war. His account confirms that enlistment in British service was often offered as an escape from starvation and disease aboard prison ships—but many refused, even under overwhelming odds.

Source: Ethan Allen, A Narrative of Colonel Ethan Allen’s Captivity (1779).

Despite the overwhelming odds, resistance never fully disappeared. Prisoners whispered plans, shared scraps of food, and clung to the hope of exchange.

A small number managed to escape, sometimes aided by sympathetic civilians, including patriot women like Elizabeth Burgin, who risked her life to help men flee captivity. These acts of defiance, however rare, became lifelines in a place designed to extinguish hope.

By the end of the war, the death rate aboard the Jersey and other prison ships was staggering. More Americans died in British captivity in Wallabout Bay than in all Revolutionary War battles combined. For survivors, the memory of the Jersey never faded.

It stood as proof that the struggle for American independence was not only fought with muskets and cannons, but endured in silence, darkness, and unimaginable suffering—where simply staying alive became an act of patriotism.

British Policy, Prison Hulks, and the Machinery of Captivity

The British use of prison ships during the Revolutionary War was not the product of battlefield improvisation or local excess alone. It rested on an existing legal and administrative framework that predated American independence.

In May 1776, as tensions with the American colonies escalated toward open rebellion, the British Parliament passed what became known as the Hulks Act. The legislation authorized the confinement of prisoners aboard decommissioned ships moored in British waters, primarily as a response to overcrowded jails and the suspension of transportation to penal colonies.

The idea of prison ships was normalized by the British Parliament

Though intended for British convicts on the River Thames, the Act normalized the idea that prison ships were a lawful and acceptable substitute for land-based incarceration.

When British authorities in North America faced a surge of captured Americans after the fighting around New York, they drew upon this precedent. The conversion of aging warships and transport vessels into floating prisons was not controversial within British command circles; it was a familiar solution applied in a new theater.

Official correspondence from British naval and commissary offices treated prison ships as routine logistics. Prisoners were “disposed of on board the hulks,” “removed to the Jersey,” or “confined to the prison ships,” language that reduced human beings to administrative problems rather than moral concerns.

The absence of commentary on suffering in these records was not accidental—it reflected a system focused on containment, not care.

The British use of prison ships in the Revolutionary War was not merely an improvised response to overcrowding in New York City. In 1776, Parliament passed the Hulks Act, authorizing confinement aboard decommissioned ships (“hulks”) as a lawful substitute for land prisons. Although aimed at British convicts in Britain, the policy helped normalize prison hulks as an accepted solution across the empire.

British correspondence and administrative language often treated captives as logistics—men “disposed of” on the hulks, “removed” to specific vessels, or “confined” to prison ships. At the same time, the British government frequently classified captured Americans as rebels rather than conventional prisoners of war, avoiding any implication that the United States was a legitimate sovereign opponent. That distinction mattered: it reduced the customary restraints that might otherwise have governed the treatment of prisoners of war.

Ships such as the HMS Jersey operated within this policy framework—officially designated, guarded, and supplied, yet often leaving the human cost unmeasured. The result was a detention system that could be lawful on paper and catastrophic in practice.

Research note: This section summarizes widely documented British policies and record-keeping practices of the late 18th century, including Parliament’s Hulks Act (1776), British classification of American captives as rebels, and routine naval correspondence regarding prison hulks and prison ships.

Underlying this system was a deliberate political position taken by the British crown and government. Captured Americans were frequently classified not as enemy soldiers, but as rebels engaged in an internal insurrection.

Granting them formal prisoner-of-war status would have implied recognition of American sovereignty—something British officials were unwilling to concede, particularly in the early years of the conflict.

This legal distinction had profound consequences. Without POW recognition, American captives were excluded from the customary protections afforded to enemy soldiers under 18th-century norms, including adequate rations, medical attention, and timely exchange.

New Jersey was officially designated a prison ship

The operation of the HMS Jersey illustrates how this policy translated into lived reality. British administrative records confirm that the Jersey was officially designated as a prison ship, staffed with guards, and supplied through standard channels.

Yet those same records are conspicuously silent on mortality. Deaths were not systematically recorded, nor were conditions meaningfully inspected. The ship functioned as an endpoint in the British detention system—a place to warehouse prisoners indefinitely. The lack of oversight was itself a form of policy. By failing to measure suffering, British authorities avoided responsibility for it.

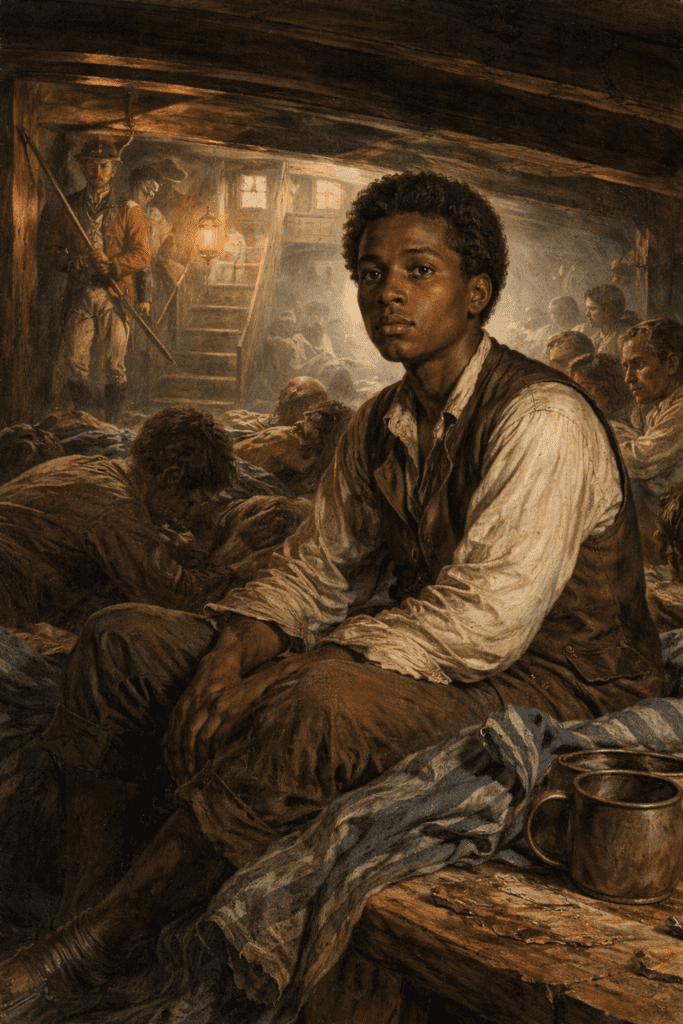

James Forten (above), an African American sailor captured during the Revolutionary War, survived imprisonment aboard the British prison ship HMS Jersey. His experience reflects the brutal conditions faced by American prisoners in Wallabout Bay and the resilience of those who endured captivity in the fight for independence.

Together, these elements formed a machinery of captivity that was lawful under British statutes, efficient in administrative terms, and devastating in human cost. The prison ships of Wallabout Bay were not accidents of war; they were the predictable outcome of legislation, classification, and indifference.

When American leaders like George Washington protested conditions and warned of reciprocal treatment, they were not responding to isolated abuses but to a system deliberately constructed to operate beyond the limits of compassion.

As the United States approaches its 250th anniversary, understanding this framework matters. It reminds us that the suffering endured aboard British prison ships was not merely the result of cruelty by individual guards or officers, but the consequence of policy decisions made far from the holds of the ships themselves—decisions that allowed thousands of men to die unseen, unheard, and largely unrecorded.

1. The Hulks Act of 1776 (British Parliament)

📜 What it is

The most important British document is the Hulks Act, formally titled:

“An Act for the better securing and maintaining of offenders convicted of certain crimes” (16 Geo. III c.43, 1776)

Passed by Parliament in May 1776, just weeks before the Declaration of Independence.

📌 What it authorized

- The use of decommissioned ships (“hulks”) as floating prisons

- Originally intended for British convicts on the River Thames

- Authorized hard labour, confinement, and long-term detention aboard ships

- Established prison ships as a legal, administrative solution to overcrowded jails

⚠️ Why it matters for your article

Although the Act was written for Britain, it:

- Created legal precedent for prison ships

- Normalized the idea that ships could replace prisons

- Made it easy for British commanders in North America to extend the practice to:

- American prisoners

- Privateers

- Sailors

- “Rebels” not recognized as POWs

You can accurately say:

“When British authorities turned to prison ships in New York Harbor, they were drawing on a system already sanctioned by Parliament itself.”

2. British Naval & Commissary Correspondence (1776–1783)

📜 What exists

There are numerous British military and naval letters that:

- Refer to prisoners being “put on board the hulks.”

- Discuss provisioning, guarding, and transporting prisoners

- Treat prison ships as routine logistics, not moral dilemmas

These appear in:

- Admiralty records

- Commissary General correspondence

- British officers’ letters and diaries

They often use language like:

- “disposed of on board the prison ships.”

- “confined to the hulks.”

- “removed to the Jersey”

📌 Important nuance

These documents rarely describe conditions in emotional terms.

Instead, they reveal something more chilling:

- Prisoners are treated as inventory

- Suffering is implied through shortages, not acknowledged directly

That contrast strengthens your narrative when paired with:

- Washington’s protest letter

- Ethan Allen’s testimony

- Philip Freneau’s poem

3. British Justification: “Rebels,” Not POWs

📜 Policy position

The British government consistently argued:

- American captives were rebels, not enemy soldiers

- Recognizing them as POWs would imply recognition of American sovereignty

This position appears in:

- Parliamentary debates

- Official correspondence

- British proclamations

📌 Why this matters

It explains:

- Why were POW protections denied?

- Why prison ships could be so harsh

- Why did Washington invoke reciprocal treatment in his letters

You can accurately write:

“By denying American prisoners formal POW status, British authorities removed legal and moral restraints on their confinement.”

4. The HMS Jersey and British Administrative Records

While no single British document says “let them die”, records show:

- The Jersey was officially designated a prison ship

- Guards, rations, and oversight were assigned

- Deaths were not systematically recorded — itself a policy decision

The absence of concern in official records becomes evidence in itself.

Exchange, Endurance, and the Long Road to Freedom

For most American prisoners held aboard British prison ships, escape was rare and survival uncertain. While civilians like Elizabeth Burgin provided extraordinary assistance to a fortunate few, the overwhelming majority of captives remained trapped by policy, geography, and the course of the war itself.

British authorities tightly controlled prisoner movement, and the East River, guarded shorelines, and armed patrols made escape attempts perilous.

Those who failed often faced harsher confinement or death.

Prisoner exchanges offered another path to freedom, but they were inconsistent and politically fraught. Early in the Revolutionary War, the British government resisted formal exchanges, maintaining that captured Americans were rebels rather than legitimate prisoners of war.

This position stalled negotiations and left thousands of men languishing aboard prison ships long after their capture. Only as the conflict dragged on—and international pressure mounted—did exchanges become more common, though never sufficient to relieve overcrowding or suffering on a large scale.

The Continental Congress and Continental Army attempted to negotiate exchanges through intermediaries, but progress was slow. British officers prioritized their own soldiers and sailors, while American seamen and privateers—captured in especially large numbers—were often treated as expendable.

Many prisoners waited months or even years for release, surviving only through resilience, mutual aid among fellow prisoners, and the hope that the war itself might end before they did.

Even after the war was over, the British continued to hold prisoners

That hope was realized only gradually. Even after the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781, prison ships in New York Harbor continued to hold American captives. The British occupation of New York City lasted until November 1783, nearly two years after the decisive battle. During that time, disease, starvation, and neglect continued to claim lives aboard the hulks anchored in Wallabout Bay.

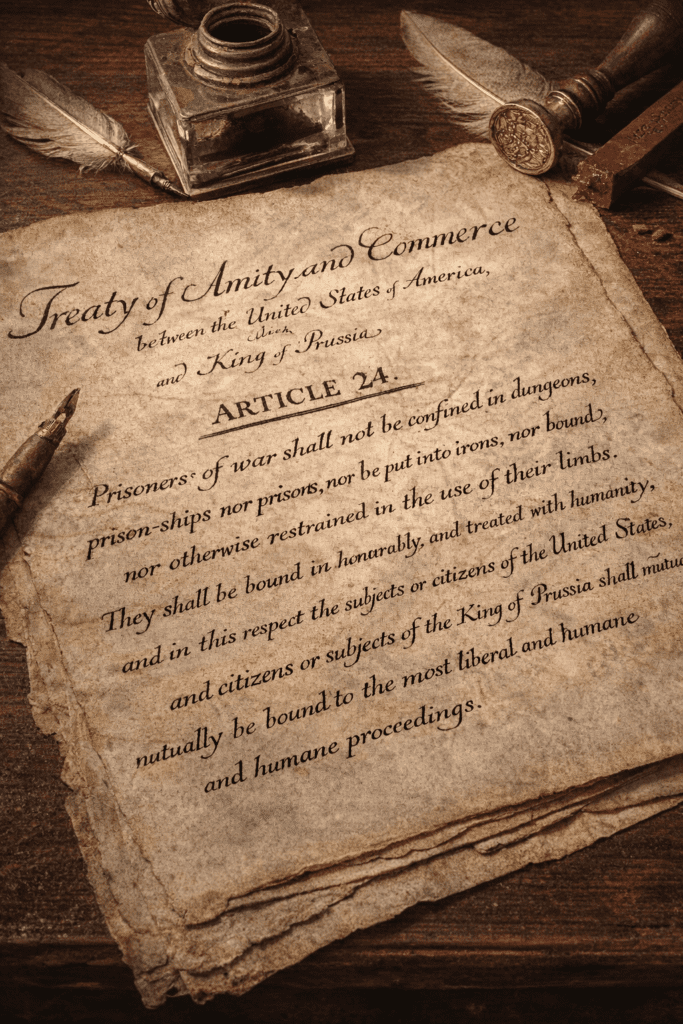

In 1785—just two years after the end of the Revolutionary War—the United States and Prussia signed a treaty that quietly acknowledged the suffering endured by American prisoners. Article 24 established one of the world’s earliest humanitarian rules governing the treatment of prisoners of war.

The language was unmistakable. The horrors of British prison ships—especially those anchored in New York Harbor— had left such a mark that the new United States moved to ensure the practice would never be repeated. As America approaches its 250th anniversary, Article 24 stands as proof that the suffering of the prison ship martyrs helped shape the nation’s earliest commitment to humane treatment in war.

When the end finally came, it was not marked by celebration aboard the prison ships. Of the many thousands who had entered captivity during the war, only a fraction survived to walk free. The survivors emerged weakened, scarred, and often forgotten—while the dead were left in shallow graves along the Brooklyn shoreline, their sacrifice unrecorded in official British accounts.

As the United States approaches its 250th anniversary, this chapter of the Revolutionary War reminds us that independence was not secured in a single moment or place.

It was earned through endurance—by soldiers in battle, by civilians who risked everything to help others, and by prisoners who survived overwhelming odds in the darkest corners of the war. The prison ships of Wallabout Bay stand as a stark testament to the human cost of freedom, and to those whose suffering helped shape the nation that would emerge in 1783.

From Prison Hulks to Principles: What the Prison Ships Taught a New Nation

The British prison ships of the Revolutionary War were not aberrations born solely of cruelty or neglect. They were the predictable outcome of policy. Parliamentary authorization under the Hulks Act normalized confinement aboard ships.

British administrative correspondence treated prisoners as logistical problems rather than human beings. The refusal to recognize captured Americans as legitimate prisoners of war removed customary restraints on their treatment. And ships like the HMS Jersey operated within an official system that measured supplies and security—but not suffering.

Yet the legacy of the prison ships did not end with British evacuation or the close of the war. Their impact shaped how the United States understood both independence and responsibility.

American leaders who had witnessed captivity firsthand—men like George Washington, John Adams, and others—carried those lessons into diplomacy. They understood that victory without principle was hollow, and that the moral authority of the new nation would depend on how it treated even its enemies.

That understanding found expression in law. In 1785, just two years after the war’s end, the United States negotiated the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with Prussia. Article 24 of that treaty explicitly forbade the confinement of prisoners in prison ships, dungeons, or irons.

It was a quiet but unmistakable response to the suffering endured in places like Wallabout Bay. The language did not name the British prison ships, but it did not need to. The lesson had been learned, written into the earliest framework of international humanitarian law.

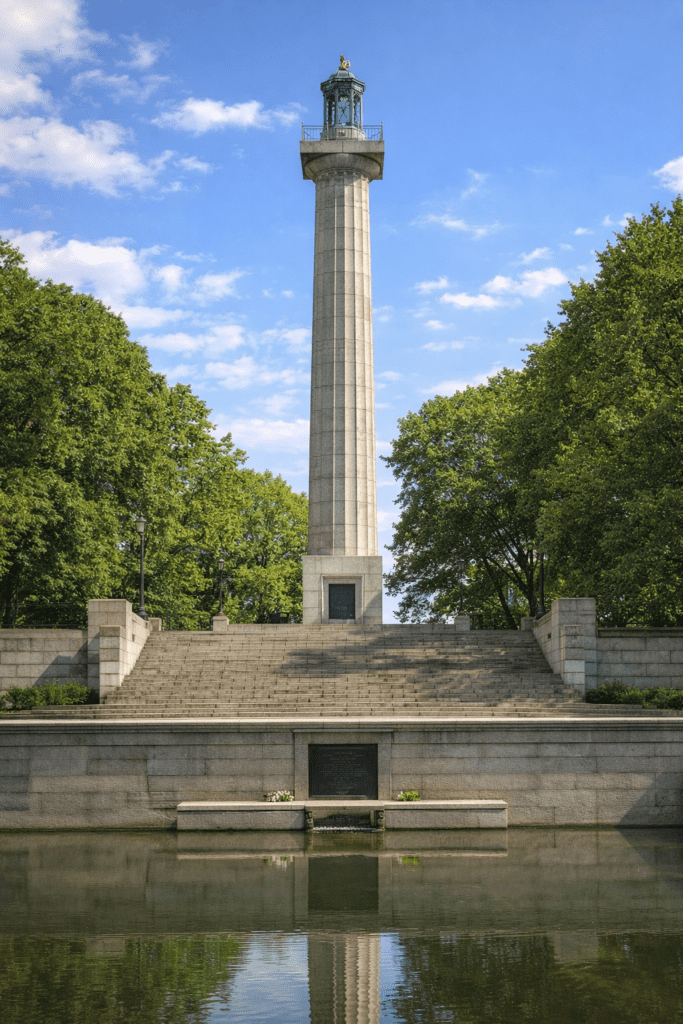

At the same time, remembrance took physical form. The bones that washed ashore along Brooklyn’s waterfront could not be ignored. Civic organizations, state authorities, and national leaders eventually sanctioned the burial and memorialization of the prison ship dead.

The Prison Ship Martyrs Monument at Fort Greene Park stands not as an accusation, but as an acknowledgment—a recognition that thousands of Americans died in captivity and that their sacrifice mattered. Nations do not build monuments for forgotten suffering.

British silence after the war is itself revealing. There was no formal denial, no inquiry that refuted the accounts of survivors, no defense of the prison ships as humane or necessary. The practice simply faded away. What replaced it—codified protections for prisoners of war—stands as an unspoken admission that the system had failed.

The suffering endured aboard British prison ships during the Revolutionary War exposed a brutal truth: without clear rules, prisoners become invisible. Captivity without accountability allowed neglect, disease, and starvation to flourish unchecked. The prison ships demonstrated that cruelty does not always require intent—only indifference reinforced by policy.

It would take decades—and many more wars—before the international community acted decisively. Early steps, such as the 1785 treaty banning prison ships, showed that lessons had been learned. But it was not until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that those lessons were fully codified in international law.

The Geneva Conventions did not emerge suddenly; they were built slowly upon the accumulated memory of past abuses. The prison ships of Wallabout Bay stand among the earliest warnings that humane treatment of prisoners must be guaranteed by law—not left to circumstance, convenience, or the character of individual captors.

As the United States approaches its 250th anniversary, the story of the prison ships reminds us that independence was not secured solely through battlefield triumphs or celebrated declarations. It was forged through endurance, resistance, and the willingness to learn from suffering.

The men who died aboard the prison ships of Wallabout Bay did not live to see the nation they helped create. But the principles that emerged from their captivity—human dignity, restraint in war, and remembrance—remain among the most enduring legacies of the American Revolution.

Their suffering was not in vain. It became law. It became a memory. And at 250 years, it remains a warning and a promise.

Thousands of American prisoners are confined aboard British prison ships anchored at Wallabout Bay, including the HMS Jersey. Disease, starvation, and neglect lead to death rates higher than battlefield losses during the Revolutionary War.

British forces evacuate New York City. Survivors of the prison ships are released, while thousands of the dead remain buried in shallow graves along the Brooklyn shoreline.

The new United States helps establish one of the earliest international rules for humane treatment of prisoners of war, explicitly banning confinement in prison ships, dungeons, and irons.

International law formally recognizes protections for wounded soldiers and medical personnel, marking the beginning of modern humanitarian law.

Protections are extended to prisoners of war and civilians, codifying standards that address abuses first exposed during earlier conflicts, including the prison ship era of the American Revolution.

Why it matters: The suffering aboard Revolutionary War prison ships did not disappear into history. It became part of the accumulated memory that shaped international law—proof that humane treatment of prisoners had to be guaranteed, not assumed.

Conclusion: Remembering the Prison Ships at America’s 250th Anniversary

The story of the British prison ships stands among the most sobering chapters of the Revolutionary War—and one of the most instructive. Anchored quietly in places like Wallabout Bay, these vessels became sites of mass suffering not because of a single act of cruelty, but because of policy decisions, legal classifications, and indifference to human cost.

Parliament authorized prison hulks, British authorities labeled American captives as rebels rather than prisoners of war, and administrative systems tracked supplies and security while leaving suffering unmeasured.

As historian Edwin G. Burrows documents in Forgotten Patriots (https://www.basicbooks.com/titles/edwin-g-burrows/forgotten-patriots/9780465008353/), more Americans died in captivity during the Revolutionary War than were killed in combat—a fact that reshapes how we understand the true cost of independence.

Yet the prison ship era did not end in silence or irrelevance. Survivors carried their memories forward through memoirs, letters, and testimony that refused to let the dead vanish into anonymity. Civilians such as Elizabeth Burgin risked their lives to aid prisoners, while leaders like George Washington protested conditions even as the war continued. British policy, however, remained largely unchanged until the conflict itself ended.

As historian Alan Taylor has noted in his broader examination of the early republic and the British Empire (https://wwnorton.com/books/American-Republics/), imperial wartime practices often treated prisoners as expendable assets rather than human beings—an approach that left deep scars on both sides of the Atlantic.

After the war, the new United States responded not with vengeance, but with principle. In 1785, just two years after independence, American diplomats helped craft the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with Prussia. Article 24 of that treaty explicitly banned the confinement of prisoners in prison ships, dungeons, or irons—a direct response to the suffering endured aboard vessels like the Jersey.

The full text of the treaty, preserved by Yale Law School’s Avalon Project (https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/prus1785.asp), shows how quickly the young nation sought to turn lived trauma into lasting legal reform. Though modest in length, Article 24 stands among the earliest international acknowledgments that humane treatment of prisoners must be guaranteed by law, not left to circumstance or convenience.

Remembrance followed reform. The bones that washed ashore along Brooklyn’s waterfront could not be ignored, and civic organizations, state authorities, and national leaders eventually sanctioned their burial and memorialization.

The Prison Ship Martyrs Monument at Fort Greene Park stands today not as an accusation, but as an acknowledgment. As earlier generations understood, nations do not build monuments for imagined wrongs. They build them to confront uncomfortable truths and to honor sacrifices that shaped the country’s moral foundations (https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/fort-greene-park/highlights/19618).

As the United States approaches its 250th anniversary, remembering the prison ships matters more than ever. Independence was not secured only by famous battles or celebrated declarations.

It was earned through endurance—by soldiers, sailors, civilians, and prisoners who survived overwhelming odds, and by those who did not. Their suffering helped shape principles that still guide international law and human conscience today.

At 250 years, the prison ship martyrs remind us that freedom carries responsibility: to remember, to learn, and to ensure that even in war, humanity is never treated as expendable.

This prison-ship story is one chapter in a much larger national journey. Visit our hub for more 1776–1783 history, timelines, and new articles added throughout the year.

Tap a question to expand the answer.

1) What were British prison ships during the Revolutionary War?

2) Why did the British use prison ships instead of land prisons?

3) Where was Wallabout Bay, and why is it central to this story?

4) What was the HMS Jersey, and why was it called the “Old Jersey Prison Ship”?

5) What were conditions like aboard British prison ships?

6) Were American privateers and Continental Navy sailors treated differently?

7) Did prisoners have any choices, such as joining the British Navy?

8) Who was Philip Freneau, and why is his account important?

9) Were there escape attempts, and how did Elizabeth Burgin help prisoners?

10) What did the United States do after the war to prevent prison ship abuses?

Discover more from RetireCoast.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.