Last updated on December 26th, 2025 at 05:44 pm

SECTION 1 — Introduction: The Forgotten Half of the American Revolution

When most people imagine the Revolutionary War, they picture ragged Continental soldiers firing muskets across smoky battlefields. What rarely comes to mind are the thousands of women, children, laborers, and family members who marched beside them. These individuals—known today as camp followers Revolutionary War—performed essential, often dangerous work that kept the Continental Army alive. Far from idle observers, these women cooked, laundered, nursed, carried water and supplies, and sometimes even took up arms themselves.

1.1 Women in Warfare Before 1776

Long before Lexington and Concord, women accompanied armies across Europe and the colonies. This was not unusual—it was a practical necessity. Many enlisted men had wives and children who depended on them for survival. Rather than stay behind in poverty or danger, families followed the regiments.

In the Revolutionary War, women traveled with the Continental Army because:

- Their husbands enlisted and left them with no means of support

- They provided essential labor that the army could not replace

- They were often safer with the army than in contested regions

- George Washington recognized that soldiers fought better when their families were cared for

These women formed the backbone of daily camp life. Their work determined whether a regiment marched, ate, or survived the winter.

Primary Source Spotlight

To understand the real experience of these women, historians often turn to rare firsthand testimonies. One of the most valuable comes from Sarah Osborn Benjamin, who served for years with the army and left a detailed pension declaration:

— Sarah Osborn Benjamin, pension testimony, 1837

Her account directly contradicts the old assumption that women stayed far from danger. She describes standing close enough to see cannon fire—close enough that a single misstep could have ended her life.

1.2 Myth vs. Reality

For generations, traditional historians portrayed camp followers as nuisances or burdens. Victorian writers, in particular, cast them in an unfair and often moralizing light. One widely read historian, Benson J. Lossing, wrote in 1860:

— Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution, 1860

This view—based on Victorian social expectations, not historical evidence—shaped public understanding for more than a century.

Modern research tells a very different story:

Myth: Women were simply “tag-alongs.”

Reality: They provided labor the army desperately needed—cooking, washing, nursing, hauling supplies, and maintaining camp operations.

Myth: Women stayed behind the battle lines.

Reality: Many women, like Sarah Osborn, were in the line of fire, delivering water and ammunition during battles.

Myth: Women weakened morale.

Reality: Officers noted that women stabilized camp life, improved morale, and enabled soldiers to focus on combat.

These myths persisted only because early historians ignored firsthand accounts like Sarah Osborn’s and instead repeated assumptions rooted in later social norms.

Part of the America 250 Series

This article is part of RetireCoast’s 250th Anniversary Hub , a growing collection of articles exploring life in 1776 and the people who forged a new nation. These pieces focus on individuals, events, and realities you likely did not encounter in traditional history books.

Companion Reading

Our companion article, Camp Followers of the Revolutionary War , is essential reading and leads directly into this article. If you want the complete story of how the Continental Army survived—and why women were indispensable—it is a must-read.

1.3 Why History Ignored Them

Women of the Revolutionary War were largely erased not because they were unimportant, but because their roles did not fit the heroic, male-centered military narrative favored at the time.

Several factors contributed to their near disappearance from history:

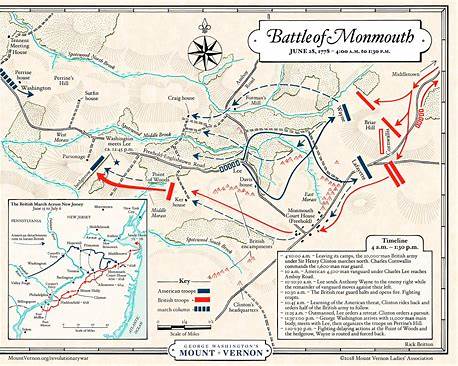

- They could not formally enlist, so their names rarely appeared in military records

- Pension laws originally excluded women, delaying recognition for decades

- Early historians prioritized generals and battles, not daily life or support roles

- Victorian morality made it socially unacceptable to portray women near soldiers

- Many women were poor and illiterate, leaving few written records

Only when researchers analyzed pension files, court declarations, and soldiers’ letters in the 19th and 20th centuries did the truth finally emerge:

Women were indispensable to the fight for independence.

When I began researching material for RetireCoast’s series on the 250th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, I was struck by how tightly woven the lives of citizen soldiers and their families truly were. The more I read, the more it became clear that women carried an extraordinary and often invisible burden during the Revolutionary War.

I started talking with people about what I was discovering, and not one person I spoke with had any real awareness of these women or their sacrifices. Because distant relatives of mine were engaged in the Revolutionary War, I felt compelled to tell their story—especially the story of the women whose labor, courage, and endurance made independence possible.

That sense of responsibility resonates deeply with me. During World War II, my mother worked in a tank factory, a reminder that across generations, American women have stepped forward when history demanded it—often without recognition, but never without impact.

The audio below is a personal reflection expanding on why this history matters today.

SECTION 2 — Margaret “Captain Molly” Corbin

2.1 Early Life on the American Frontier

Margaret Corbin was born Margaret Cochran around 1751 in what is now Franklin County, Pennsylvania—a dangerous frontier region during the French and Indian War. Her childhood was shaped by violence and loss. When Margaret was still young, her parents were killed during a raid, leaving her orphaned and hardened by circumstances few modern Americans can imagine.

This early exposure to hardship forged the resilience that would later define her place in American history. Like many frontier women, Margaret learned to endure physical labor, danger, and uncertainty as part of daily life.

She later married John Corbin, an artilleryman in the Continental Army. When he enlisted, Margaret followed him—not as a passive observer, but as a camp follower who cooked, washed, and supported the artillery company.

2.2 The Battle of Fort Washington (November 16, 1776)

The Battle of Fort Washington was one of the darkest moments of the Revolutionary War. Located on the northern tip of Manhattan, the fort was intended to delay British control of the Hudson River. Instead, it became the site of a crushing American defeat.

As British and Hessian forces attacked from multiple directions, American defenders were overwhelmed. Artillery units were critical to slowing the advance—and dangerously exposed.

When John Corbin was killed while manning a cannon, Margaret did something extraordinary.

She stepped directly into his place.

Under intense fire, Margaret loaded and fired the cannon alongside the remaining artillery crew. Witnesses later testified that she continued operating the gun until she was struck by grapeshot.

Her injuries were catastrophic:

- Her left shoulder was shattered

- Her arm was nearly torn from its socket

- Her chest and jaw were badly wounded

She collapsed beside the cannon she had refused to abandon.

The audio below explains why Mary Ludwig Hays matters even when parts of her story blend memory and legend. While later generations turned her into “Molly Pitcher,” contemporary accounts confirm that women carried water, served artillery crews, and remained under fire at Monmouth. This audio separates what can be verified from what was later romanticized—and why both shaped how Americans remembered women of the Revolutionary War.

2.3 Aftermath: Wounds, Poverty, and Recognition

Margaret survived—but her life was permanently altered. She was left partially disabled, unable to fully use her arm, and suffered chronic pain for the rest of her life.

Unlike many women whose service went unrecognized, Margaret’s actions were so undeniable that the Continental Army could not ignore them. In 1779, Pennsylvania granted her a lifelong pension—making her the first woman in American history to receive a military pension for combat service.

She later lived at West Point among disabled veterans, a rare acknowledgment that her service placed her alongside wounded soldiers—not behind them.

2.4 Legacy at West Point

Margaret Corbin’s legacy endured long after she died in 1800. She was buried with military honors, and today she is memorialized at West Point, where a monument recognizes her as a woman who fought, bled, and sacrificed for American independence.

Her story shatters the myth that women of the Revolutionary War remained safely behind the lines. Margaret Corbin did not merely support the fight—she stood in the path of it.

She represents a truth that history long resisted acknowledging:

When the Revolution demanded courage, American women answered.

When I began researching material for RetireCoast’s series on the 250th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, I was struck by how tightly woven the lives of citizen soldiers and their families truly were. The more I read, the more it became clear that women carried an extraordinary and often invisible burden during the Revolutionary War.

I started talking with people about what I was discovering, and not one person I spoke with had any real awareness of these women or their sacrifices. Because distant relatives of mine were engaged in the Revolutionary War, I felt compelled to tell their story—especially the story of the women whose labor, courage, and endurance made independence possible.

That sense of responsibility resonates deeply with me. During World War II, my mother worked in a tank factory, a reminder that across generations, American women have stepped forward when history demanded it—often without recognition, but never without impact.

The audio below is a personal reflection expanding on why this history matters today.

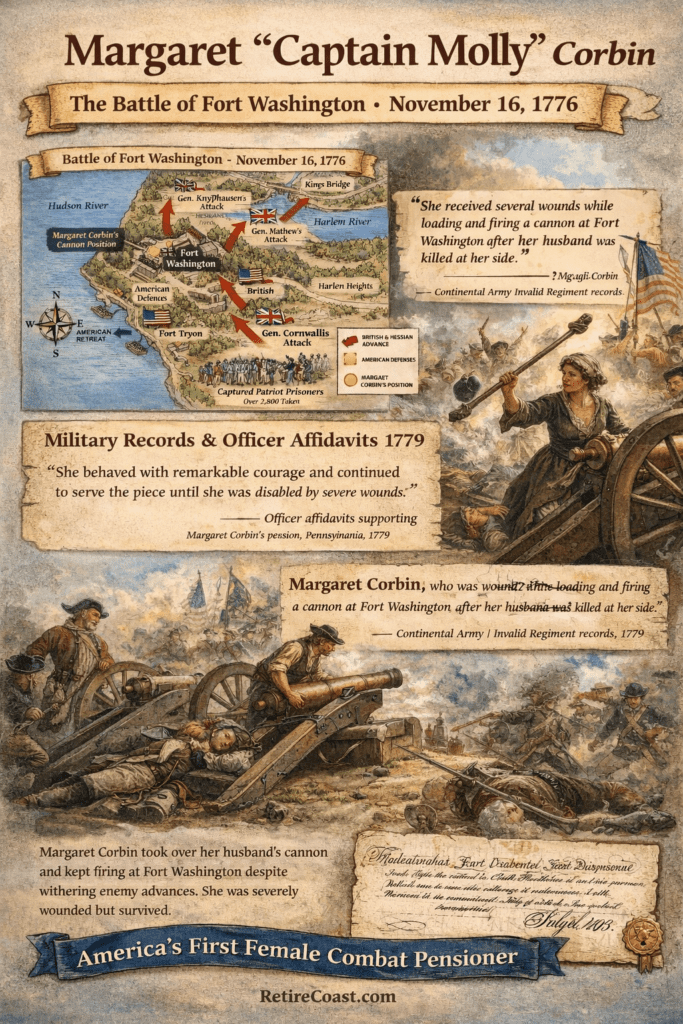

This infographic combines period-style battle scenes, a tactical map of Fort Washington, and excerpts from contemporary military records documenting Corbin’s courage and injuries while operating an artillery cannon after her husband was killed. Her service was later officially recognized with a military pension.

This print-ready PDF includes a fully illustrated infographic of Margaret “Captain Molly” Corbin at the Battle of Fort Washington (1776), combining a battlefield map, period-style artwork, and excerpts from contemporary military records.

Tip: On mobile, the PDF opens in a new tab—use the share icon to save or print.

The audio below is a third-party reading of contemporary military records describing Margaret Corbin’s actions at the Battle of Fort Washington. These are not later legends or patriotic retellings—they are drawn from official rolls, sworn officer affidavits, and government recognition created within years of the battle.

- Continental Army / Invalid Regiment records (1779)

- Officer affidavits supporting Margaret Corbin’s pension (1779)

- Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council relief and pension action (1779)

This audio reinforces the historical record by presenting what soldiers, officers, and government authorities documented about Corbin’s courage under fire.

SECTION 3 — Mary Ludwig “Molly” Hayes and the Birth of a Legend

3.1 The Woman Behind “Molly Pitcher.”

Unlike Margaret Corbin, whose service is confirmed through military rolls and pension records, Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley occupies a more complicated place in Revolutionary War history. She was a real woman, married to an artilleryman, present with the army—and almost certainly involved in combat support during battle. What history debates is how much of what we call “Molly Pitcher” belongs to her alone, and how much represents the shared experience of many women.

“Molly” was a common nickname for Mary, and “Pitcher” referred to the water vessels women carried to cool cannons and hydrate soldiers. In that sense, Molly Pitcher was never just one person—it was a role.

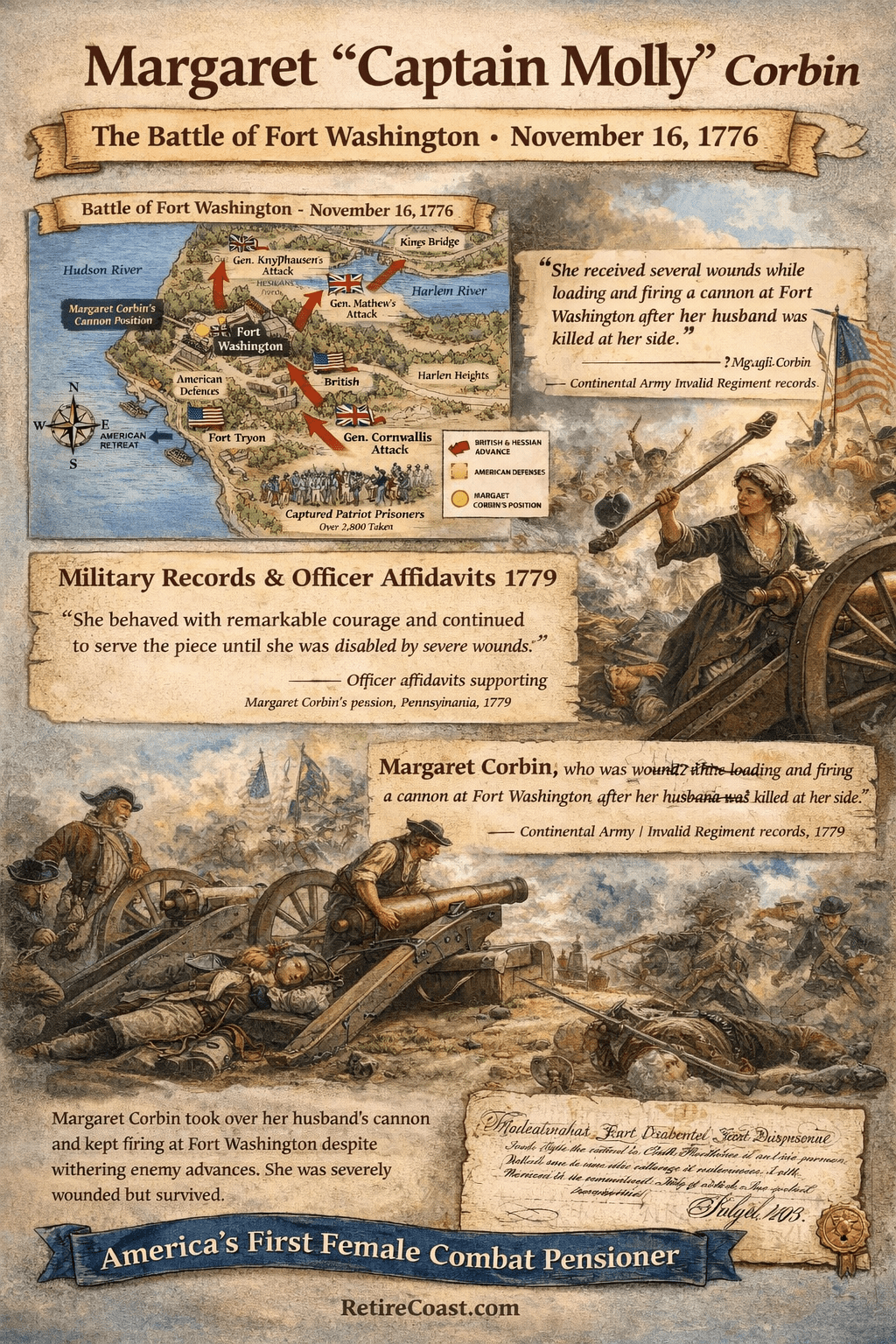

3.2 The Battle of Monmouth (June 28, 1778)

The Battle of Monmouth, fought in brutal summer heat in New Jersey, tested the Continental Army’s discipline and endurance. Artillery units were especially vulnerable, operating in open fields under direct fire.

Mary Ludwig Hays was there, bringing water to the gun crews. According to multiple later accounts, her husband collapsed—either from heat exhaustion or wounds—and Mary stepped forward to assist at the cannon.

What is credible and widely accepted:

-

- Women carried water to artillery crews during Monmouth

-

- At least one woman assisted or replaced a fallen artilleryman

-

- George Washington personally observed women near the guns

What is less certain:

-

- Whether Mary Ludwig alone fired the cannon

-

- Whether Washington formally commissioned her

-

- Whether the famous quote “Sergeant Molly” was ever officially spoken

The absence of immediate military paperwork does not negate her presence—but it does require caution.

- Women carried water to artillery crews during the Battle of Monmouth.

- At least one woman assisted or replaced a fallen artilleryman under fire.

- Mary Ludwig Hays was present with the army and later received a Pennsylvania pension.

- George Washington observed women performing support duties near the guns.

- A formal battlefield promotion to sergeant by Washington.

- A single named woman performing all artillery actions.

- Direct quotations attributed to Washington at the cannon.

- Immediate Continental Army documentation of her service.

Historical takeaway: “Molly Pitcher” represents a real and repeated role performed by women during

the Revolution. While later retellings simplified the story into a single heroic figure, the underlying service was genuine.

3.3 Washington’s Recognition: Fact vs Tradition

Later retellings claim that George Washington promoted Mary to sergeant on the field. There is no surviving written order confirming this. However, there is evidence that Washington tolerated—and at times encouraged—the presence of women performing essential duties near the lines.

In the decades after the war, Mary received a small annual pension from Pennsylvania, described as compensation for services rendered during the Revolution. While modest, this payment reinforces that her contribution was acknowledged locally, even if it never appeared in Continental Army records.

3.4 How a Shared Experience Became a Single Hero

By the mid-19th century, writers and artists sought simple, symbolic heroes. The figure of Molly Pitcher—a woman calmly firing a cannon amid chaos—fit perfectly.

Victorian-era histories merged:

-

- Margaret Corbin’s documented artillery service

-

- Mary Ludwig’s presence at Monmouth

-

- The everyday labor of countless unnamed women

…into a single, patriotic icon.

This process did not diminish women’s contributions—it blurred them.

3.5 Why Molly Pitcher Still Matters

Even when separated from embellishment, Mary Ludwig Hays represents something essential:

Women were not passive witnesses to the Revolution.

They were:

-

- Close enough to battle to be wounded or killed

-

- Trusted with critical tasks under fire

-

- Integral to artillery operations

-

- Seen—and remembered—by those who fought beside them

Molly Pitcher is not important because every detail is provable.

She is important because the role she represents was real, repeated, and indispensable.

SECTION 4 — Sarah Osborn: A Woman Who Left the Record Behind

4.1 An Ordinary Woman in Extraordinary Circumstances

Sarah Osborn does not appear in patriotic paintings or battlefield monuments. She did not become a legend. What makes her historically invaluable is something rarer: she left a clear, sworn record of her service.

Sarah Osborn followed the Continental Army for years, accompanying her husband—and later continuing service after his death. Unlike many women whose contributions were absorbed into anonymity, Osborn later testified in detail about what she did, where she went, and how long she served.

Her words allow historians to reconstruct daily life in the army with uncommon precision.

4.2 What Sarah Osborn Actually Did

In her pension testimony, Sarah Osborn described work that was constant, exhausting, and essential. She did not frame her service as heroic—she described it as necessary.

Her duties included:

-

- Cooking for soldiers

-

- Washing and mending clothing

-

- Carrying water and provisions

-

- Preparing food during active campaigns

-

- Remaining with the army through marches and battles

Most importantly, she made clear that this work occurred in proximity to combat, not far behind the lines.

“I was with the army… I carried water to the men to drink and to make their coffee. I was in sight of the firing the whole time.”

This single sentence dismantles the idea that women were safely removed from danger.

4.3 Yorktown: Women at the Decisive Moment

Sarah Osborn was present during the Siege of Yorktown, the campaign that effectively ended the Revolutionary War.

She crossed rivers with the army, endured shortages, and continued feeding soldiers while artillery bombarded British positions. Her testimony places women inside the logistical engine of victory at its most critical moment.

Yorktown was not only won by known generals—it was sustained by people like Sarah Osborn, whose labor kept troops functioning during weeks of siege warfare.

4.4 Why Her Testimony Matters More Than Legend

Unlike Molly Pitcher, Sarah Osborn does not require interpretation or reconstruction. Her testimony was:

-

- Sworn

-

- Reviewed

-

- Accepted by government authorities

-

- Preserved in pension records

For historians, this makes her one of the strongest primary sources we have for understanding women’s roles during the Revolutionary War.

She confirms that:

-

- Women stayed with the army for years, not days

-

- Their labor was expected and relied upon

-

- They were present during major engagements

-

- Their service was later recognized—quietly, but officially

4.5 The Women History Forgot—But the Records Did Not

Sarah Osborn represents thousands of women whose names appear only once—in pension files, affidavits, or court records. These documents lack drama, but they tell the truth.

She reminds us that the Revolution was not only fought by famous figures and symbolic heroes, but by ordinary people who endured hardship without expectation of recognition.

If Margaret Corbin proves women fought, and Molly Pitcher shows how women were remembered, Sarah Osborn proves how women worked—and were documented.

SECTION 5 — Beyond the Famous Names: Other Women of the Revolutionary War

5.1 Deborah Sampson — Fighting Disguised as a Man

Deborah Sampson enlisted in the Continental Army disguised as a man and served for more than a year under the name Robert Shurtliff. She marched, fought, and was wounded—removing a musket ball herself to avoid discovery.

Her service was later verified, and she received a military pension. Sampson’s story demonstrates that women did not merely support combat operations—some actively fought, even when the law forbade it.

5.2 Phillis Wheatley — The War of Ideas

Phillis Wheatley never carried a musket, but she fought a different battle: the war of ideas. An enslaved African American poet, Wheatley wrote works that challenged assumptions about intellect, liberty, and race at the very moment the colonies debated independence.

Her poetry was read by revolutionary leaders and circulated internationally. Wheatley’s contribution reminds us that the Revolution was not only military—it was philosophical, moral, and deeply contested.

5.3 Nancy Hart — Frontier Resistance

On the southern frontier, Nancy Hart became known for her resistance to Loyalist forces in Georgia. While later stories exaggerated her exploits, contemporary accounts confirm that Hart aided Patriot efforts, gathered intelligence, and confronted enemy soldiers directly.

Her story reflects the reality of irregular warfare in the South, where homes often became battlegrounds and women faced violence without the protection of formal armies.

5.4 Anna Maria Lane — Wounded in Battle

Anna Maria Lane followed her husband into the war and was wounded during combat. Like Margaret Corbin, Lane later received a pension for her service and injuries.

Her case reinforces a crucial point: women were close enough to battle to be wounded, and their injuries were serious enough to warrant official recognition.

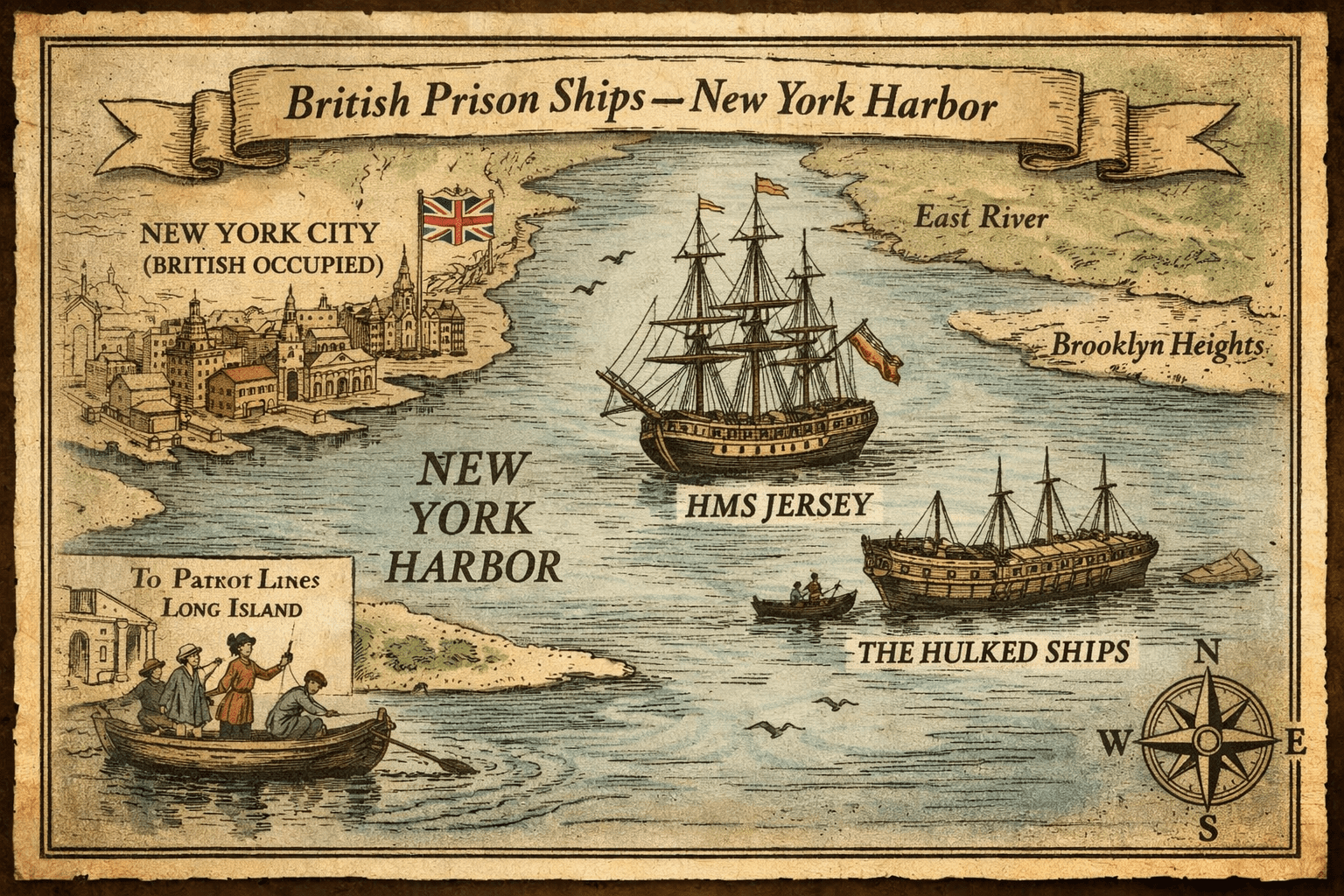

Elizabeth Burgin lived in British-occupied New York City, one of the most dangerous places for a Patriot sympathizer during the Revolutionary War. Using deception and disguise, she approached British prison ships under the pretense of delivering aid.

Contemporary accounts credit Burgin with helping dozens of American prisoners escape, often one at a time. These men faced starvation and disease aboard the prison ships anchored in New York Harbor.

When her activities were discovered, British authorities confiscated her property, forcing her to flee the city. That retaliation confirms the seriousness—and success—of her resistance.

Elizabeth Burgin and New York Harbor prison ship context

5.5 Elizabeth Burgin — Defying the British

Elizabeth Burgin used deception and courage to rescue American prisoners from a British prison ship in New York Harbor. Disguised and operating under constant threat, she helped free dozens of men who would otherwise have died in captivity.

Her actions highlight another overlooked dimension of the war: resistance did not always occur on battlefields. It also occurred in harbors, prisons, kitchens, and city streets.

5.6 Why These Women Matter Together

These women did not share the same roles, backgrounds, or recognition—but together they show the full scope of women’s involvement in the Revolutionary War:

-

- Some fought

-

- Some worked

-

- Some wrote

-

- Some resisted

-

- Some suffered wounds

-

- Some left records

-

- Many did not

What unites them is not legend, but participation.

They were not anomalies.

They were part of the fabric of the Revolution.

Women Punished — and Sometimes Executed

While women were less likely than men to face formal military trials during the Revolutionary War, they were not immune from lethal punishment. In occupied cities, frontier regions, and areas of irregular warfare, British and Loyalist authorities sometimes executed women accused of aiding the rebellion.

These executions rarely followed the procedures of formal courts-martial. Instead, they often occurred as reprisals, carried out quickly to discourage resistance. Women suspected of spying, harboring Patriot fighters, carrying intelligence, or assisting escapes faced imprisonment, property confiscation, exile—and in some cases, death.

The historical record is fragmentary. Many of these women were civilians, and their names were seldom recorded in official military documents. What survives instead are local accounts, pension affidavits, and postwar testimony, which confirm that women were sometimes killed deliberately as examples.

British authorities generally preferred lesser punishments—confiscation of property, public humiliation, or forced displacement—but execution was used when officials believed a woman posed an ongoing threat or could not be controlled by other means.

The scarcity of names does not mean the acts did not occur. It reflects the reality of 18th-century recordkeeping, where women’s resistance was often punished quietly and remembered imperfectly.

This final truth completes the picture: women did not merely support the Revolution. Some resisted openly, some covertly—and some paid with their lives.

The death of :contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0} in 1777 became one of the most widely publicized civilian killings of the Revolutionary War. McCrea was killed near Fort Edward, New York, by Native allies of the British during the Saratoga campaign.

Although she was not executed following a formal trial, her death was widely attributed to failures of British command and became a powerful Patriot propaganda symbol. Her case illustrates how civilian women could become lethal casualties of British-aligned operations—even when they were not combatants.

Women accused of aiding the rebellion were usually civilians, not soldiers. Punishments were often carried out without formal trials, especially in occupied cities and frontier regions. As a result, executions and killings were rarely entered into centralized military records. What survives instead are fragments—local accounts, confiscation records, pension affidavits, and postwar testimony.

Download & Share This Image

This image was created as part of RetireCoast’s America250 series and may be downloaded for educational, classroom, or commemorative use.

⬇ Download ImageImage credit: RetireCoast · America’s 250th Anniversary Series

Conclusion — What the Women of the Revolutionary War Teach Us

The women of the Revolutionary War were not footnotes to history. They were participants, woven into every layer of the conflict. Some fought. Some worked. Some resisted. Some were punished. And some left records strong enough to still speak across centuries.

From Margaret Corbin, whose wounds and pension confirm that women fought at the cannon, to Mary Ludwig Hays, whose memory became the symbolic “Molly Pitcher,” to Sarah Osborn, whose sworn testimony places women in sight of the firing, the historical record is clear: women in the American Revolution were present where danger and necessity met.

The term camp followers has often diminished their role, suggesting distance from combat or importance. In reality, camp followers in the Revolutionary War formed the logistical backbone of the Continental Army. They cooked, washed, carried water, nursed the wounded, crossed rivers, endured sieges, and remained with the army for years at a time. Without them, the Revolution could not have been sustained.

Others, like Elizabeth Burgin, resisted from within enemy-occupied cities, risking execution to free prisoners from British prison ships. And in darker corners of the war, women accused of aiding the rebellion were punished—sometimes executed—leaving behind fragmentary records that still testify to the risks they took.

Together, these stories dismantle the myth that the Revolution was fought only by men with muskets. They reveal a broader truth: Revolutionary War women were not passive witnesses to independence—they were active agents in its creation.

As we approach the 250th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, this history matters more than ever. Remembering the women of the Revolutionary War is not about rewriting history. It is about completing it.

Their courage was real.

Their labor was essential.

Their sacrifice helped give birth to a nation.

Author’s Note

This article was written as part of RetireCoast’s ongoing work surrounding the 250th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. In researching the women of the Revolutionary War, one truth became impossible to ignore: our nation was sustained not only by famous names and battlefield victories, but by ordinary women who endured extraordinary hardship.

Their stories deserve to be remembered with accuracy, respect, and humility.

— RetireCoast Editorial Team

The Military Women’s Memorial, located at Arlington National Cemetery, honors the women who have served—and continue to serve—this nation in uniform. It stands as a living bridge between the women of the Revolutionary War and those who followed in every generation since.

Learn more at: womensmemorial.org | Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR)

1) Who were the “women of the Revolutionary War”?

2) Did women actually fight in the American Revolution?

3) Who was Margaret Corbin and why is she important?

4) Was “Molly Pitcher” a real person or a legend?

5) What were “camp followers” in the Revolutionary War?

6) What is Sarah Osborn known for?

7) Who was Elizabeth Burgin and what did she do?

8) Were women ever punished or executed by British or Loyalist forces?

9) Why are there fewer written records about women in the American Revolution?

10) Where can I learn more or continue the America250 series?

Opens the full episode in a new window

Discover more from RetireCoast.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.