Last updated on February 16th, 2026 at 07:37 pm

250th Anniversary Series

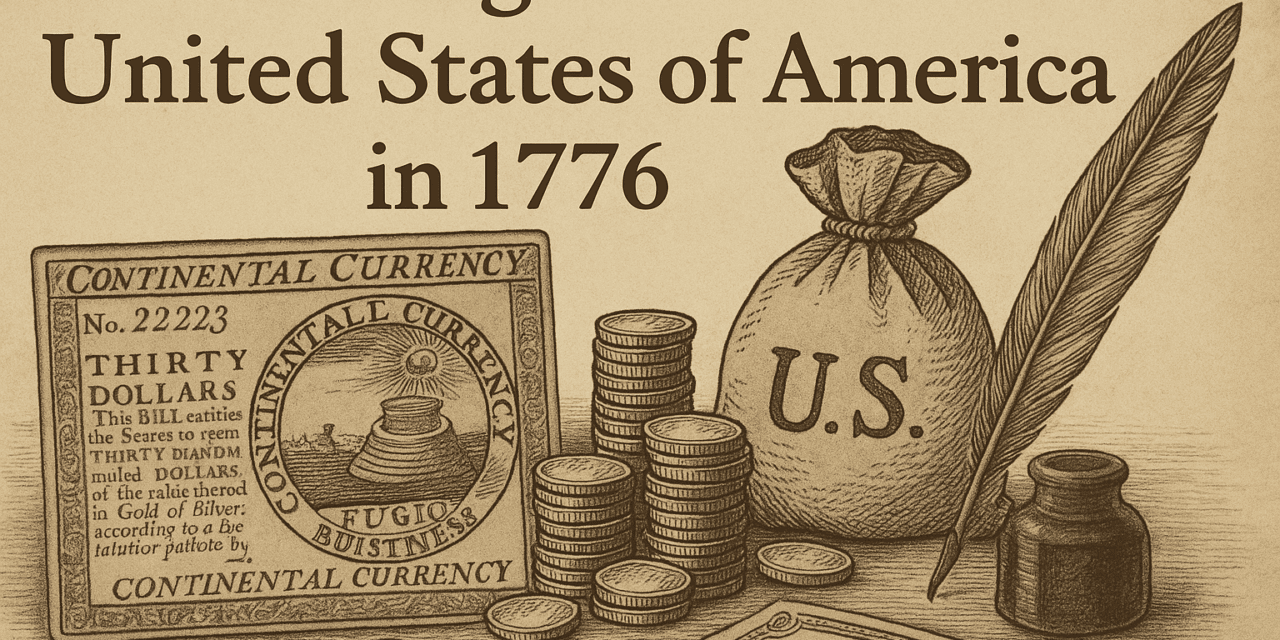

Financing the New United States of America

This article is part of an ongoing series produced by RetireCoast.com in celebration of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, which will be observed on July 4, 2026. Our goal is to explore the people, places, and pivotal events that shaped the founding of the United States. From colonial life and Revolutionary War milestones to the legacies we carry today, each article in this series helps connect the past with the present. Visit our USA 250th Anniversary Cornerstone Page for the full collection.

The Continental Congress had no power to tax

According to historian John Steele Gordon in An Empire of Wealth: The Epic History of American Economic Power, the finances of the fledgling United States in 1776 were nothing short of disastrous. The Continental Congress had no power to tax, no central bank, and no reliable stream of income.

Instead, it issued paper currency—”Continental dollars”—that quickly became worthless, giving rise to the phrase “not worth a Continental.” Inflation soared, and confidence in the currency plummeted.

By the time independence was declared, the colonies were already deeply in debt. They had borrowed heavily to finance local militias and defensive efforts during the early years of resistance to British rule. Once the Revolutionary War was underway, funding came from foreign loans—especially from France, Spain, and the Netherlands—but those loans came with interest and political strings.

Each state issued its own currency

At the state level, finances weren’t much better. Each state issued its own currency and levied its own taxes, leading to widespread confusion and a lack of uniform value. Some states refused to collect taxes altogether, and others relied heavily on printing money.

Commerce, once regulated by the British imperial system, now fell into chaos, with tariffs and trade restrictions between states threatening to strangle the fragile economy before it could grow.

Smuggling flourished

Smuggling flourished during and after the war. Rhode Island, a small but fiercely independent state with a robust maritime economy, became a haven for smugglers avoiding British duties—and later, any federal regulation that threatened local profits. It’s no wonder that Rhode Island was the only state that refused to send a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

The state’s leaders feared that a stronger federal government would clamp down on their lucrative trade, much of which skirted legal boundaries.

The first national bank was created – The Bank of North America

Before and after 1776, financing the war and managing national debt became central issues of debate. Prominent figures like Robert Morris, appointed Superintendent of Finance in 1781, attempted to impose fiscal discipline. Morris created the first national bank—the Bank of North America—modeled after the Bank of England.

Though controversial, it became a cornerstone of early American finance and laid the groundwork for future federal monetary institutions.

Meanwhile, the burden of war fell heavily on ordinary Americans. Taxes were levied in goods instead of money; soldiers were paid in near-worthless currency; and inflation made food and basic goods prohibitively expensive. In some areas, public auctions were held to sell confiscated loyalist land, helping replenish public coffers but also sparking local resentment and instability.

The post-war years, often called the “Critical Period,” tested the very survival of the republic. Without a reliable system to raise funds, pay debts, or manage interstate commerce, the Articles of Confederation proved inadequate.

Federal control over monetary policy was critical

The financial chaos—along with diplomatic weakness and internal unrest like Shays’ Rebellion, ultimately pushed delegates toward the Constitutional Convention in 1787, where establishing federal control over monetary policy became a key pillar of the new government.

As we reflect 250 years later, it’s remarkable that a nation born broke, fractured, and without a centralized financial plan evolved into the world’s largest economy. The seeds of that transformation were planted during the desperate years of revolution—through makeshift currencies, emergency loans, and the vision of leaders determined to build not just a new government, but a functioning, prosperous economy.

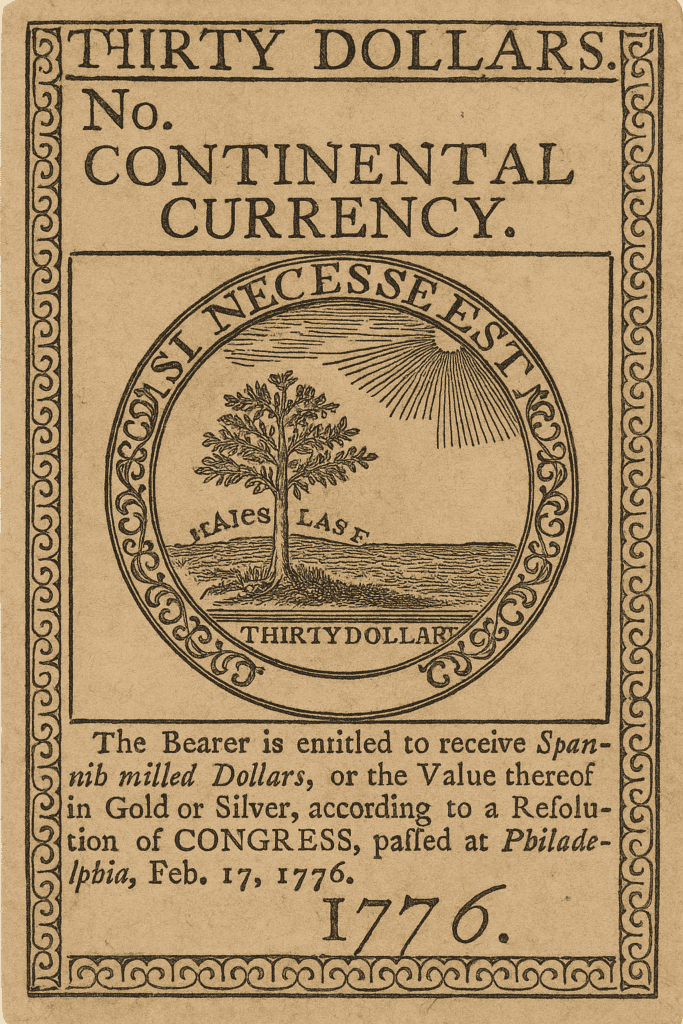

🧾 How Many Continental Currency Notes Were Printed?

Between 1775 and 1779, the Continental Congress authorized the printing of approximately $241 million in Continental Currency—a massive amount for the time and far more than the economy could support.

- These notes were issued in denominations from $1 to $80.

- There were 11 series of emissions, and millions of notes were printed in total.

- The printing was done using engraved copper plates or hand-set type and was vulnerable to counterfeiting, including by the British as a tactic to destabilize the U.S. economy.

By 1781, the value of Continental Currency had collapsed so dramatically that the phrase “not worth a Continental” became widely used.

💰 What Is a Continental Currency Note Worth Today?

The value of an original Continental Currency note as a collector’s item depends on several factors:

* 1. Denomination and Design

- Some denominations and symbols (like those with Franklin’s “Fugio” sundial or nature emblems) are rarer and desirable.

🔹 2. Condition

- Notes in uncirculated or extremely fine condition are worth significantly more.

- Worn, faded, or torn notes are common and less valuable.

🔹 3. Authentication

- Counterfeits were common even during the war, and some were crude British forgeries. Authentic notes are more desirable.

🏷️ Estimated Collector Values (as of 2025)

| Condition | Typical Value Range (USD) |

|---|---|

| Poor / Damaged | $30 – $80 |

| Fine | $100 – $300 |

| Extremely Fine | $400 – $1,200+ |

| Rare Varieties | $1,500 – $5,000+ |

For example, A 1776 $30 note (like the one in your graphic) in very fine condition might sell for $250–$500, while a rare issue or signature variant could exceed $1,000.

Tariffs Then and Now

250th Anniversary of the Nation Series

As this is written, tariffs are again at the forefront of national conversation—debated on television, in the media, and across social platforms. The return of tariffs as a political and economic talking point has prompted renewed interest in their historical role in shaping the United States’ economy.

President Donald Trump recently reminded the public that, prior to World War II, tariffs provided the bulk of general revenue for the federal government. This is historically accurate. In fact, for over a century following the nation’s founding, tariffs were the primary source of income for the United States.

According to historian John Steele Gordon, writing in the Imprimis journal published by Hillsdale College in May 2025, the formal system of tariffs began in 1790 when Alexander Hamilton, then the newly appointed Secretary of the Treasury—not Secretary of State—laid the foundation for the young nation’s fiscal policy.

Alexander Hamilton laid the foundation of fiscal policy

Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures not only encouraged domestic industry but also introduced a detailed schedule of tariffs and excise taxes on goods such as alcohol, tobacco, sugar, and select imports. His aim was twofold: to raise revenue for a nearly bankrupt national government and to protect fledgling American industries from more established European competition.

In those early decades, tariffs were considered both a financial and patriotic necessity. The Tariff Act of 1789, one of the first laws passed by Congress, levied duties on imported goods to stabilize the nation’s finances after the Revolutionary War.

By the mid-19th century, tariffs were generating up to 90% of all federal revenue—enough to fund infrastructure, maintain the military, and even support westward expansion without relying on income taxes, which didn’t exist until the early 20th century.

Tariffs funded the government

But tariffs were not without controversy. They often divided the country geographically and economically. Industrial states in the North typically supported high tariffs to protect domestic manufacturing, while Southern agricultural states opposed them, arguing they raised costs and invited retaliatory measures from trading partners.

These tensions came to a head in the Tariff of Abominations (1828), sparking the Nullification Crisis and foreshadowing the deeper sectional conflicts that would later lead to civil war.

Fast forward to today, and tariffs once again stir debate. Proponents argue that they protect American jobs and industries from unfair foreign competition. Critics contend that tariffs raise consumer prices, disrupt supply chains, and provoke trade wars. In our globally integrated economy, the impact of tariffs is far more complex than it was in Hamilton’s time.

Still, the roots of the conversation stretch back to the founding years of the Republic. As we reflect on 250 years of American history, it’s clear that debates over trade, industry, and government revenue have never strayed far from the national stage. Tariffs, once a cornerstone of the young nation’s survival, remain a powerful symbol of the balancing act between economic independence and global commerce.

Revenue Sources Were Few in 1776

250th Anniversary of the Nation Series

In 1776, as the United States declared its independence, it faced not only a military struggle but also a daunting financial vacuum. The new nation had no national bank, no standardized currency, and virtually no domestic industry capable of sustaining an economy, let alone a war.

Shipbuilding was one of the few industrial strengths in the colonies, but even that relied on British-made tools and materials. Nearly all other manufactured goods, from textiles to metal wares, were imported from England.

The British government had gone to great lengths to ensure that the colonies remained dependent on the mother country. They restricted the export of industrial machinery and banned the migration of skilled mechanics who might replicate the technologies that powered Britain’s industrial growth.

British factories bought American cotton, tobacco, and more

The colonies were to supply raw materials—like cotton, tobacco, timber, and indigo—and in return purchase finished goods from British factories. This system enriched the empire while keeping the colonies economically subordinate.

As a result, when independence came, the U.S. found itself rich in natural resources but poor in productive capacity. Without a tax base built on industry or commerce, and with only rudimentary financial infrastructure, the Continental Congress had to rely on loans, personal appeals for donations, and the printing of paper currency—much of which soon became worthless.

The nation “skimmed along,” as John Steele Gordon put it, surviving on borrowed time and borrowed money until more stable systems could be created.

One turning point came in 1790, with the appointment of Alexander Hamilton as the first Secretary of the Treasury. But another major milestone in America’s industrial awakening came not from policy, but from an act of bold defiance against British law.

Samuel Slater changed everything

Samuel Slater, an English apprentice in a textile mill, memorized the intricate design of spinning and weaving machines—a highly protected trade secret under British law—and fled to America. There, he helped establish the first successful textile mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, in 1793.

Often called the “Father of the American Industrial Revolution,” Slater brought with him not only technical knowledge but also the foundation for a new kind of economy—one in which American-made goods could eventually replace imported British products. As Gordon notes, Slater effectively “stole” Britain’s industrial secrets, but in doing so, he planted the seeds of American self-sufficiency.

This act of industrial espionage catalyzed the rise of textile manufacturing in New England and marked the beginning of a new revenue stream for the young republic. With domestic production came jobs, economic activity, and—critically—taxable commerce.

As we commemorate 250 years since the Declaration of Independence, it’s worth remembering that liberty alone was not enough to sustain a nation. It took risk-takers, innovators, and some well-timed theft of technology to help turn an economically dependent colony into a global industrial power.

The Growth of Banking: From Colonial Fragmentation to National Finance (Pre-1776 to 1800)

Before 1776, the American colonies had no formal banking institutions. The British Crown prohibited the establishment of banks in the colonies to prevent economic independence and ensure reliance on the British financial system.

Without banks, colonists relied on a mix of barter, foreign coins (like Spanish pieces of eight), personal credit, and colonial paper currency—often issued by local governments but prone to inflation and counterfeiting.

This lack of a unified monetary or credit system created widespread economic instability. Each colony issued its own currency, and there was no consistent exchange rate or central authority to regulate lending. Commercial transactions were risky and often dependent on trust or longstanding relationships. Large trade deals, especially those involving international parties, typically went through London banks or merchants.

1776–1789: War Finance and Economic Disarray

The Revolutionary War further exposed the economic weaknesses of the colonies. With no central bank or taxing authority, the Continental Congress financed the war by issuing “Continental Currency”—paper money that quickly depreciated.

Rampant inflation and lack of confidence in the government’s ability to back its currency led to economic chaos. Soldiers were paid in nearly worthless notes, and the phrase “not worth a Continental” became common.

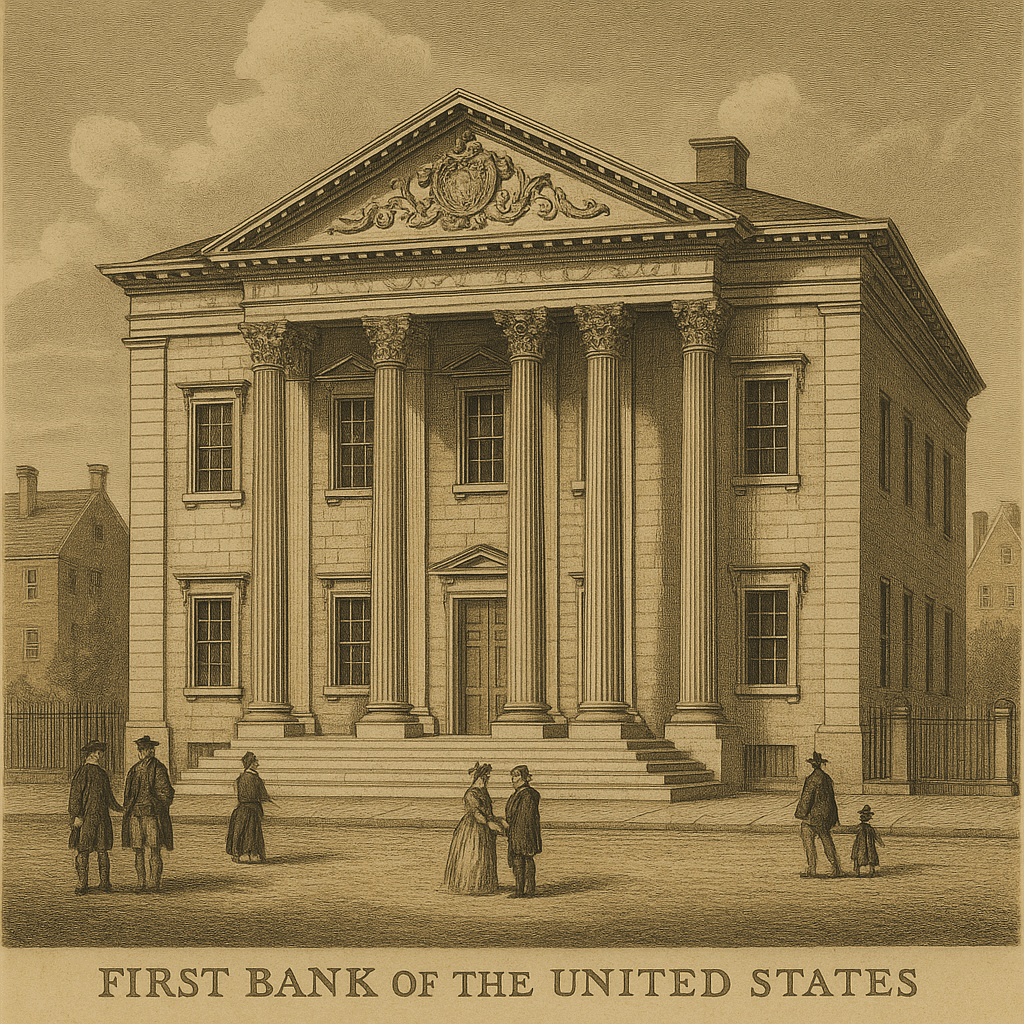

To stabilize wartime finances, Robert Morris, Superintendent of Finance, championed the idea of a national bank. In 1781, the Bank of North America was chartered in Philadelphia. It became the first official commercial bank in the U.S. and served as a prototype for national financial management. Although privately owned, it operated with the support of Congress and helped manage government deposits and credit issuance.

1790–1800: Hamilton’s Financial Revolution

With the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1789, Alexander Hamilton, the new Secretary of the Treasury, set out to build a modern financial system. His vision included:

- Federal assumption of state war debts to unify the nation’s credit.

- Creation of a national currency backed by confidence in government stability.

- Establishment of a central banking authority to manage public funds and issue loans.

In 1791, Congress passed legislation to create the First Bank of the United States, modeled loosely on the Bank of England. It was a public-private partnership with 20% government ownership and 80% private shareholders. The bank could:

- Hold federal funds

- Issue standardized banknotes

- Regulate other banks by controlling credit and monetary supply

- Provide loans to businesses and the federal government

This marked a turning point in the nation’s economic infrastructure. For the first time, the United States had a centralized financial institution capable of stabilizing currency, providing loans, and encouraging economic development.

By 1800

- A small network of state-chartered banks had begun to emerge, particularly in the Northeast.

- Public confidence in U.S. credit was rising—partly thanks to Hamilton’s controversial, but effective, policies.

- The national debate over centralized financial power had begun, with figures like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison opposing the First Bank, believing it favored Northern commercial interests over Southern agrarian ones.

Despite the political pushback, by 1800, the foundations of a modern banking system had been laid—transitioning from colonial disarray to a functioning federal economic engine. These early institutions would fuel the growth of commerce, trade, and westward expansion in the decades to come.

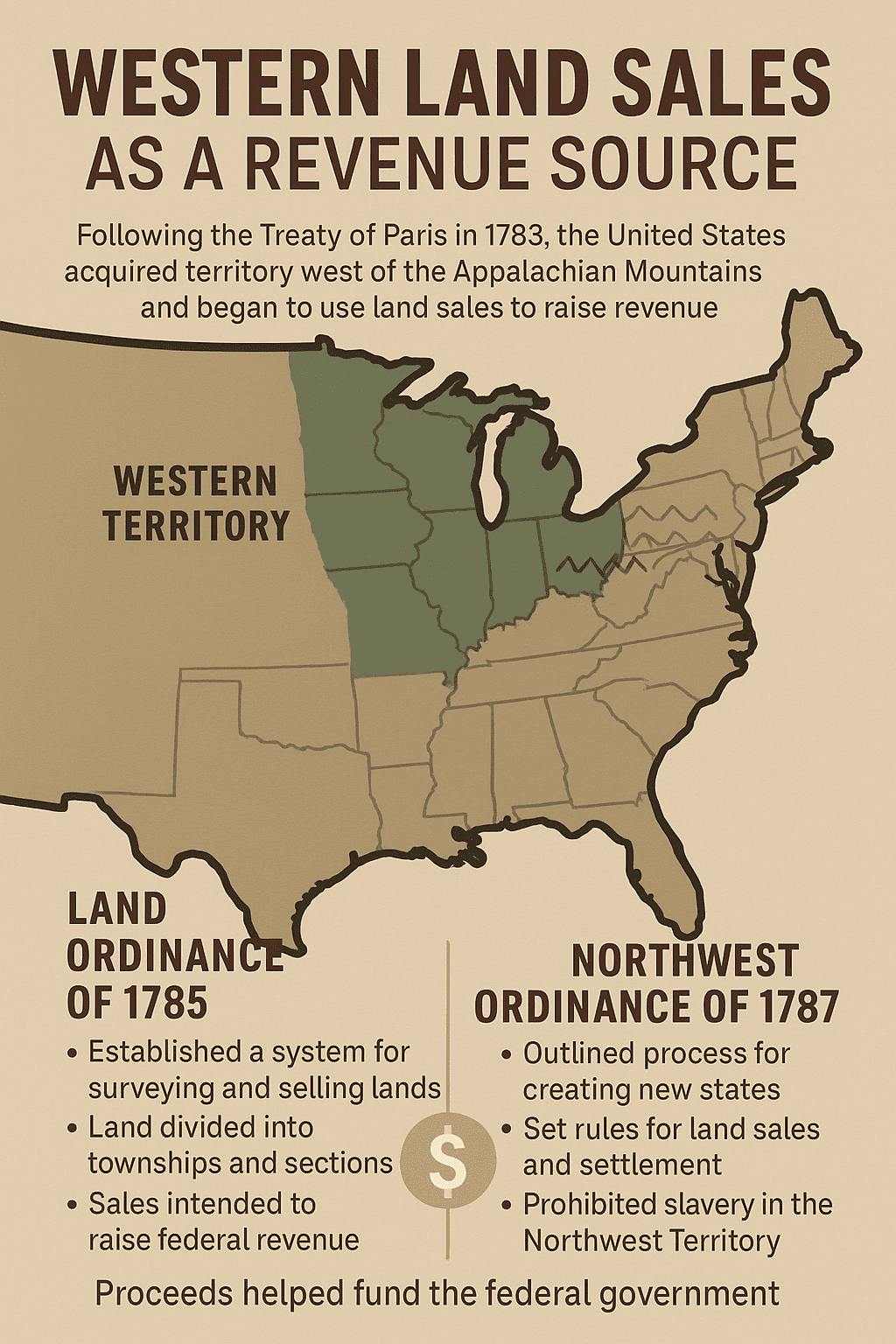

Western Land Sales as a Revenue Source

In the absence of a strong tax base or robust industry, one of the most valuable assets the young United States possessed was land—vast stretches of territory ceded by Britain under the 1783 Treaty of Paris. This western land, stretching beyond the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River, represented both opportunity and income.

The government quickly recognized that the sale of public land could become a critical source of revenue. In 1785, the Land Ordinance established a standardized system for surveying and selling land in the Northwest Territory (present-day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin).

This system divided land into townships and sections, creating an orderly method for settlement and sale that avoided many of the boundary disputes that plagued the colonies.

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 set rules

Then came the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which not only set out rules for admitting new states to the Union but also helped establish federal control over western lands. Importantly, it banned slavery in the Northwest Territory, promoted public education, and reinforced the idea that these lands would not be held as permanent colonies but would eventually become equal members of the Union.

The revenue from these land sales helped fund the federal government during a time when it lacked the authority—or infrastructure—to levy direct taxes effectively. Proceeds were used to pay down war debts, fund basic government operations, and finance future development.

Land speculation boomed

Land speculation also boomed during this period. Wealthy investors and land companies bought up large tracts of western territory, hoping to profit by reselling them to settlers and immigrants.

While this speculative fervor sometimes led to corruption and economic bubbles, it also accelerated migration, infrastructure development, and agricultural expansion—laying the groundwork for America’s transformation into a continental power.

The policy of using land as revenue wasn’t without conflict. It often came at the expense of Native American nations, who were forcibly removed or drawn into violent conflicts as settlers pushed westward. These tensions would escalate into a long legacy of displacement, broken treaties, and warfare—a tragic consequence of America’s early economic strategies.

Still, as a fiscal tool, western land sales played a vital role in keeping the new Republic afloat. They represented a uniquely American approach to economic development—one grounded not in gold or industry, but in space, opportunity, and the promise of expansion.

Note: For our friends in Mississippi, it was many years before the United States acquired Mississippi. After the acquisition, the government sold land to the public.

Explore More in the America 250th Anniversary Series

Continue your journey through 1776 with our hub and featured articles.

Frequently Asked Questions: Financing the New United States of America

1. How did the U.S. government raise money before income taxes existed?

The federal government raised revenue mainly through tariffs on imported goods and excise taxes on items like alcohol and tobacco.

2. Why did the Continental Dollar lose its value so quickly?

The government overprinted Continental Currency without gold or silver backing, which led to severe inflation and public distrust.

3. What role did Alexander Hamilton play in early U.S. finance?

Alexander Hamilton established the U.S. financial system by creating a national bank, assuming state debts, and promoting federal revenue through tariffs.

4. When did the U.S. begin selling public land for revenue?

The federal government began land sales under the Land Ordinance of 1785, using proceeds to pay war debts and fund national operations.

5. Did the U.S. government sell land on the Mississippi Gulf Coast?

Yes. After annexing West Florida and forming the Mississippi Territory, the federal government sold land there under early land acts.

6. How did tariffs support early American industries?

Tariffs protected U.S. manufacturers from foreign competition and provided essential revenue for the young federal government.

7. What was the First Bank of the United States created to do?

The First Bank issued a stable currency, managed government deposits, and regulated lending to build national credit and stability.

8. Why did some states oppose a stronger federal financial system?

States like Rhode Island feared losing economic autonomy, especially due to concerns over trade regulation and federal control of smuggling routes.

9. Who was Samuel Slater and why is he important to U.S. industry?

Samuel Slater brought British textile manufacturing techniques to America, helping launch the U.S. Industrial Revolution.

10. How does Hamilton’s financial legacy still affect the U.S. today?

Hamilton’s policies shaped central banking, credit systems, federal taxation, and economic growth strategies still used in modern America.

🇺🇸 Explore More in Our 250th Anniversary Series

This article is part of our ongoing RetireCoast historical series celebrating America’s 250th Anniversary. Visit the full hub page to explore more stories, research, and perspectives from 1776 to today.

🔗 Visit the 250th Anniversary HubDiscover more from RetireCoast.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.