Last updated on February 12th, 2026 at 08:25 pm

Who We Were in 1776: People Who Became Americans

This article is part of an ongoing series produced by RetireCoast.com in celebration of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, which will be observed on July 4, 2026. Our goal is to explore the people, places, and pivotal events that shaped the founding of the United States. From colonial life and Revolutionary War milestones to the legacies we carry today, each article in this series helps connect the past with the present. Visit our USA 250th Anniversary Cornerstone Page for the full collection.

As we prepare to celebrate the 250th anniversary250th Anniversary Hub Page of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 2026, many of us are asking: Who were the people living in the 13 colonies in 1776? What were their origins, what language did they speak, and how did they form the foundation of the United States?

This article explores the demographics and culture of colonial Americans in 1776—from where they came from to how they communicated. It’s part of our ongoing series leading to the 250th celebration and shines a light on the lives that history books often overlook. Understanding who we were helps us appreciate why the founding unfolded as it did.

- Who We Were in 1776: People Who Became Americans

- 🌍 Where Did Colonial Americans Come From?

- 🇺🇸 A Personal Connection to 1776

- ⛪ What Religions Were Practiced in 1776?

- 🗣️ What Language Did Americans Speak in 1776?

- 🛠️ Occupations and Trades in 1776: How Early Americans Made a Living

- 🌾 The Agrarian Majority: Farming Was a Way of Life

- 🧰 Skilled Trades and Artisan Professions

- 🏪 Merchants, Professionals, and the Emerging Urban Economy

- ⛓️ Enslaved and Indentured Labor: The Hidden Workforce

- 🧶 The Work of Women: Mostly Unpaid, Always Essential

- 🌍 People at the Edges of Colonial Society

- 💡 Conclusion: The Work That Built a Nation

- Without Government handouts in 1776, how did people survive?

- Were people living in the 13 colonies considered British citizens?

- 🗽 Did Colonists Automatically Become American Citizens After 1776?

- ⚖️ Citizenship After the Declaration of Independence

- 🖋️ Were Loyalty Oaths Required?

- ❌ Who Was Not Considered a Citizen?

- 📜 Citizenship After the Constitution Was Ratified (1788)

- 🧠 When Was Citizenship Officially Defined?

- 🧭 Summary: From Subjects to Citizens

- 📚 Enduring Ideas: Rights, Citizenship, and America’s Future

- 📣 Stay Connected to the USA250 Series

- FAQ

- Frequently Asked Questions About Life in 1776

- PODCAST

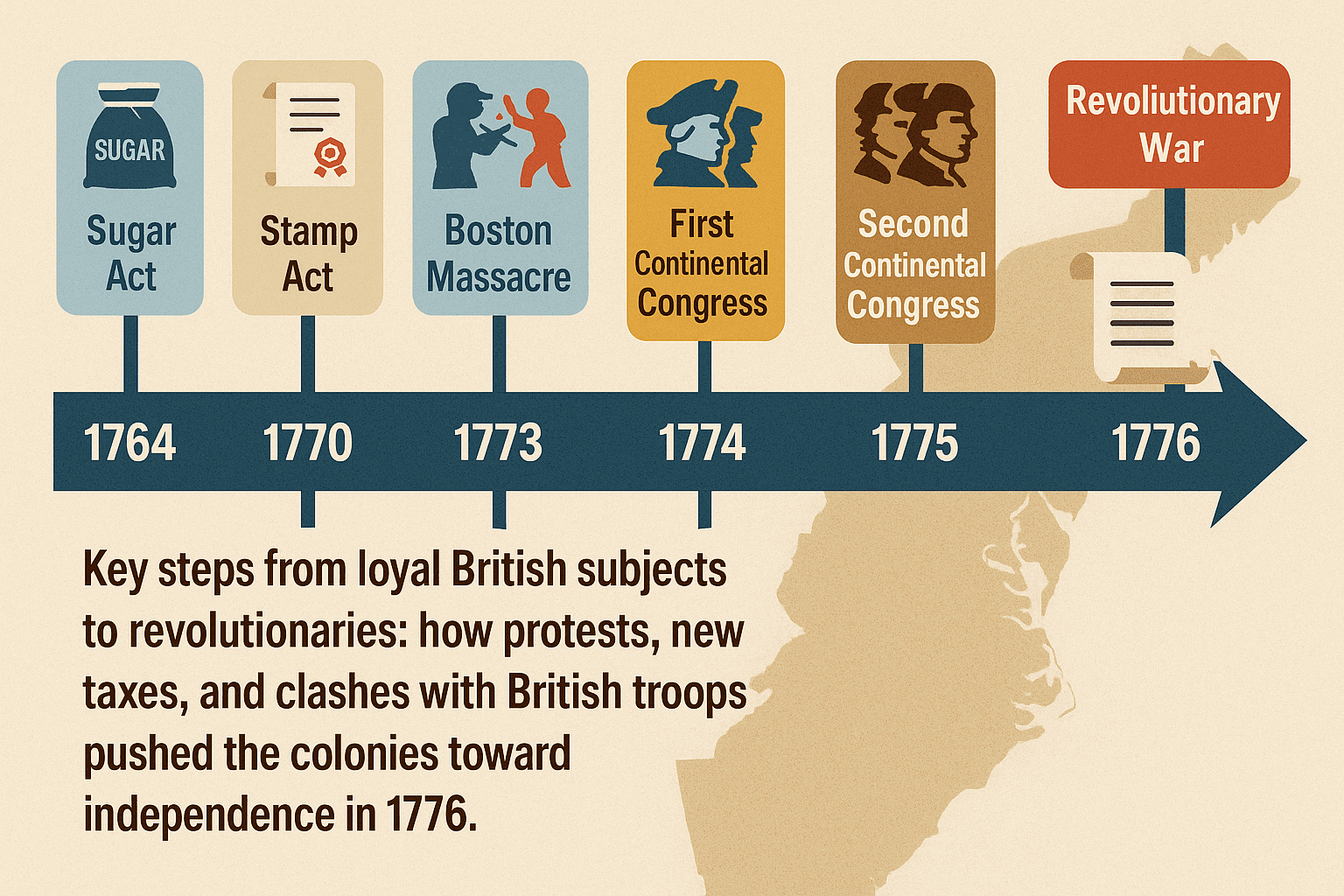

🌍 Where Did Colonial Americans Come From?

At the time of independence, the colonial population was estimated at 2.5 million people, and about 60% were of English descent. These individuals had either immigrated themselves or descended from earlier settlers. But colonial America was far more diverse than many imagine.

Key Origins of Americans in 1776:

| Ethnic Group | Estimated Share | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| English | ~60% | Dominant population across most colonies |

| Scottish & Scots-Irish | ~10–15% | Settled in the backcountry and Appalachian frontier |

| German | ~6–10% | Settled in the backcountry and the Appalachian frontier |

| Irish (Catholic) | ~5% | Urban laborers and rural poor, especially in port cities |

| Dutch | ~2% | Found primarily in New York (formerly New Amsterdam) |

| French Huguenots | ~1–2% | Protestants in South Carolina, New York, and Virginia |

| African (enslaved) | ~20% | Brought by force, mostly to the Southern colonies |

| Other Europeans | <1% | Swedes, Finns, Swiss, and others in small communities |

While most immigrants came from Europe, the population also included Native Americans who had lived on the land for generations. Though not considered citizens, they were key to trade, diplomacy, and local conflicts.

🇺🇸 A Personal Connection to 1776

One of my ancestors with my last name came to the colonies around 1714 and settled in the Philadelphia area. I have little doubt that either he or his son served in the colonial militia or even fought under General George Washington during the Revolutionary War. I haven’t yet searched the formal records to confirm enlistment, but that’s not the point I want to make here.

The point is: I have something at stake in the 250th Anniversary of the founding of the United States. As the saying goes, “I have skin in the game.” While other branches of my family didn’t arrive in America until around 1840, their lives—like all of ours today—were shaped by the risks, ideals, and sacrifices of those early colonists.

Whether your family came to the United States last year or 100 years ago, you still have a stake in what the original colonists did to make this country what it is today. We all owe a debt of gratitude. So when we celebrate July 4, 2026, let it be a national thank you—to those who came before us and made this American experiment possible.

🧠 Quiz: Who We Were in 1776

1. What was the average age of people living in the American colonies in 1776?

- A. 35 years

- B. 25 years

- C. ✅ 16 years (Half the population was under 16 due to high birth rates)

- D. 45 years

2. Which profession did the majority of colonists work in?

- A. Merchants

- ✅ B. Farming and agriculture (Over 90% worked on farms)

- C. Shipbuilding

- D. Law and politics

3. What percentage of colonists in 1776 were of British descent?

- A. 100%

- ✅ B. 60%

- C. 35%

- D. 80%

4. Which religious group dominated New England colonies?

- A. Anglican

- B. Catholic

- ✅ C. Congregationalist (Puritan)

- D. Methodist

5. What was the primary language spoken by colonists in 1776?

- A. German

- B. Dutch

- C. French

- ✅ D. English

6. Which colony was originally founded as a haven for Catholics?

- A. Virginia

- ✅ B. Maryland

- C. Massachusetts

- D. New York

7. What level of education did most colonists have?

- A. University-level education

- B. Formal secondary schooling

- ✅ C. Home or church-based literacy

- D. None

8. Which group brought Lutheran and Reformed religious traditions?

- A. French

- B. Scots-Irish

- ✅ C. Germans

- D. Dutch

9. Did all colonists automatically become U.S. citizens after 1776?

- A. Yes, instantly

- B. No, only if they signed an oath

- ✅ C. It was a gradual legal transition

- D. They remained British citizens

10. Which of these religious groups had a presence in colonial cities like Newport and New York?

- A. Amish

- ✅ B. Jewish communities

- C. Shakers

- D. Mormons

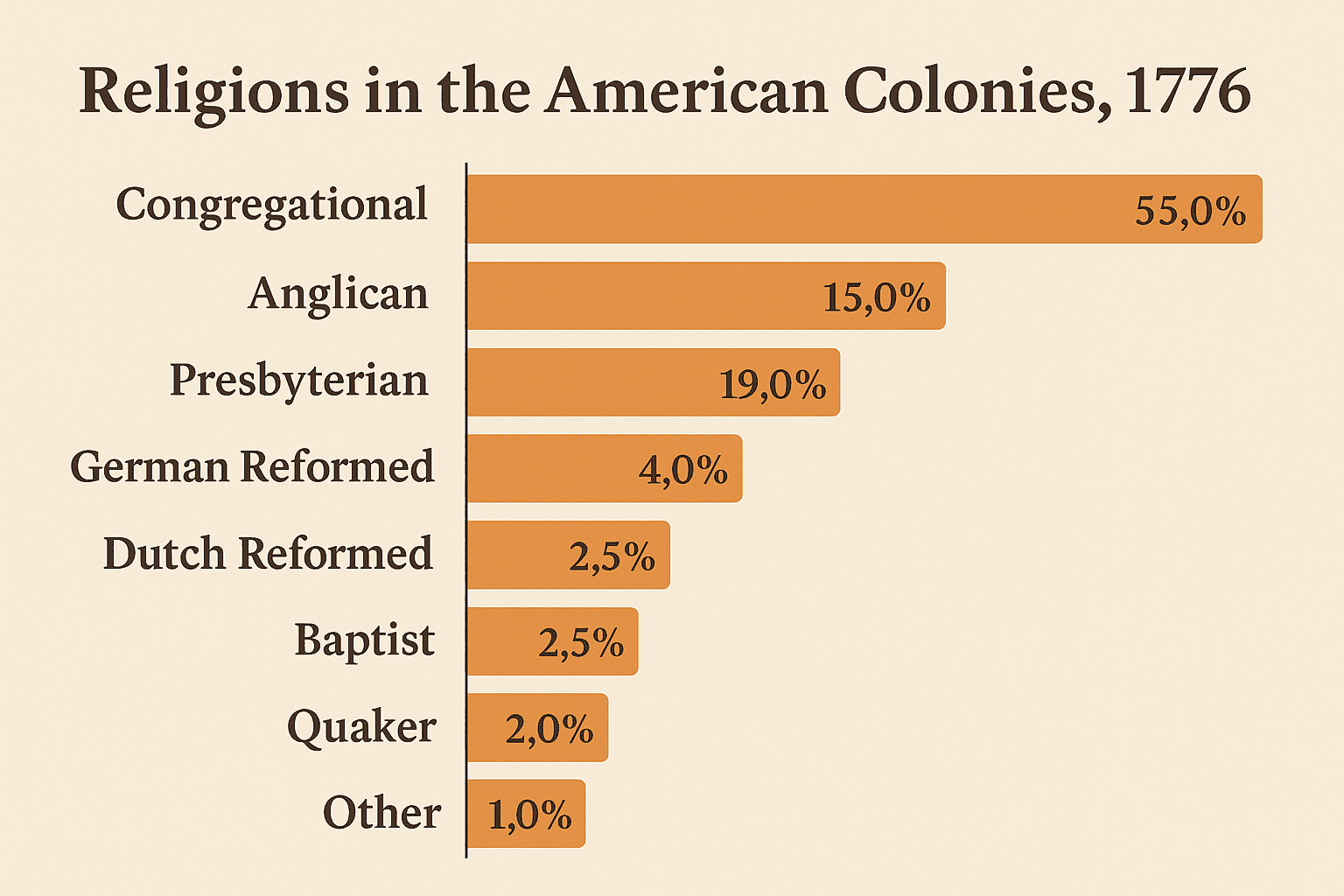

⛪ What Religions Were Practiced in 1776?

In 1776, religion shaped the daily lives, values, and institutions of most people living in the American colonies. Although the overwhelming majority of colonists identified as Christians, primarily within Protestant denominations, religious expression varied significantly from region to region. This diversity stemmed from immigration patterns, colonial charters, ethnic traditions, and differing degrees of tolerance.

According to the Library of Congress, over 98% of colonists adhered to Protestant Christianity. However, that majority encompassed many distinct sects, each with its own structure, theology, and political influence.

In colonies like Virginia, Georgia, and the Carolinas, the Anglican Church (Church of England) operated as the state-supported religion. Colonists were required to pay taxes to support Anglican clergy, and political leadership often aligned with church authority. Meanwhile, New England was dominated by Congregationalist churches, rooted in Puritan traditions.

In states like Massachusetts and Connecticut, church attendance shaped civic life, and Sunday sermons frequently included political messages that aligned with revolutionary ideals.

Religious tolerance

Moving into the middle colonies, religious tolerance became more common. In places such as Pennsylvania and parts of New Jersey, Quakers—known for their pacifism and early opposition to slavery—established influential communities. German settlers in Pennsylvania brought Lutheran and Reformed Protestant traditions, often conducting services entirely in German.

At the same time, large numbers of Presbyterians, primarily Scots-Irish immigrants, settled throughout the backcountry and Appalachian regions, building churches that served both spiritual and community needs.

By the mid-1700s, Baptists and Methodists were expanding rapidly, particularly across the South and rural frontiers. Baptists championed adult baptism and religious freedom, while Methodism, which grew out of Anglicanism, spread through traveling ministers known as “circuit riders.”

Rise of Evangelical Denominations

The rise of these evangelical denominations was largely fueled by the religious revivals of the 1700s, often referred to as the First Great Awakening. These trends are well documented by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Although small in number, Roman Catholics had established communities, particularly in Maryland, which was originally founded as a safe haven for English Catholics. However, by 1776, Maryland had shifted toward Anglican dominance.

Catholics faced legal restrictions and widespread suspicion, particularly due to ties with Catholic nations like France and Spain. As noted by U.S. Catholic magazine, Catholics made up less than 2% of the population and had limited political influence.

Jewish Communities

Jewish communities had also become part of colonial society, especially in cities such as New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, and Newport, Rhode Island. Many of these Jewish settlers descended from Sephardic Jews who had fled persecution in Spain, Portugal, and the Caribbean. The Touro Synagogue, founded in Newport in 1763, remains the oldest synagogue in the United States.

The National Museum of American Jewish History highlights how Jewish residents in Rhode Island experienced a relatively high level of religious freedom, thanks in part to the colony’s founding principles of tolerance and separation of church and state.

Among enslaved Africans, spiritual life remained deeply rooted in West African religious practices, which endured despite efforts to suppress them. While many were forcibly converted to Christianity, many retained elements of their ancestral beliefs. This blending of traditions gave rise to rich cultural expressions, such as the Gullah spiritual tradition found in coastal South Carolina and Georgia.

Some Islamic Faith

Additionally, some enslaved people brought Islamic faith and practices with them. Although slavery limited religious expression, historical records confirm that Islamic traditions persisted among enslaved Muslims. The National Museum of African American History and Culture explores these hidden religious histories in detail.

At the same time, Native American tribes continued to follow their own spiritual paths, rooted in ancestral traditions. Despite missionary efforts aimed at Christian conversion, many Native communities resisted and maintained their religious independence.

Some tribes integrated aspects of Christianity, while others preserved ceremonial life unchanged. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian provides in-depth resources on the enduring richness of Indigenous spiritual culture.

Tax dollars funded some churches

Although there was no official national religion in 1776, several colonies still maintained established churches funded by public taxes. However, the increasing religious diversity and growing desire for freedom of conscience were already shaping a new national ideal.

These developments laid the groundwork for the First Amendment, ratified in 1791, which enshrined the principle of religious liberty as a core American value.

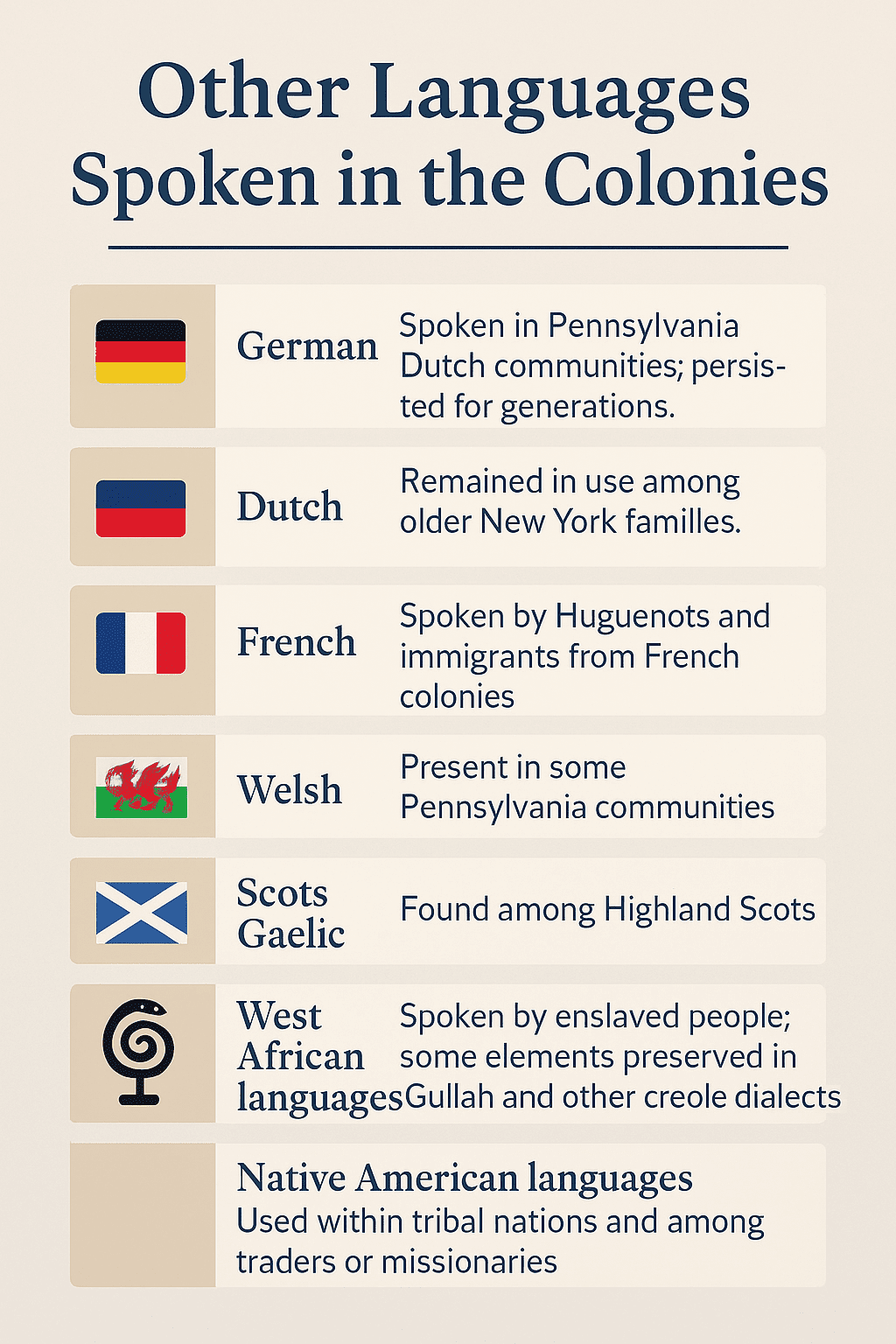

🗣️ What Language Did Americans Speak in 1776?

English was the primary language of the colonies, not only due to the majority English-speaking population, but also because it was the language of law, commerce, and colonial administration.

However, colonial America was multilingual:

Other Languages Spoken in the Colonies:

-

- German – Spoken in Pennsylvania Dutch communities; persisted for generations.

-

- Dutch – Remained in use among older New York families.

-

- French – Spoken by Huguenots and immigrants from French colonies.

-

- Welsh – Present in some Pennsylvania communities.

-

- Scots Gaelic – Found among Highland Scots.

-

- West African languages – Spoken by enslaved people; some elements preserved in Gullah and other creole dialects.

-

- Native American languages – Used within tribal nations and among traders or missionaries.

How Fast Did Non-English Speakers Learn English?

-

- In urban areas, assimilation was faster—often within a single generation.

-

- In rural communities, particularly among Germans and the Dutch, native languages remained in use for several generations.

-

- Enslaved Africans were often forced to adopt English for labor communication, though many retained linguistic traditions.

The dominance of English by 1776 set the tone for its role as the future national language, but the multilingual foundation of the early U.S. reveals a more complex cultural heritage.

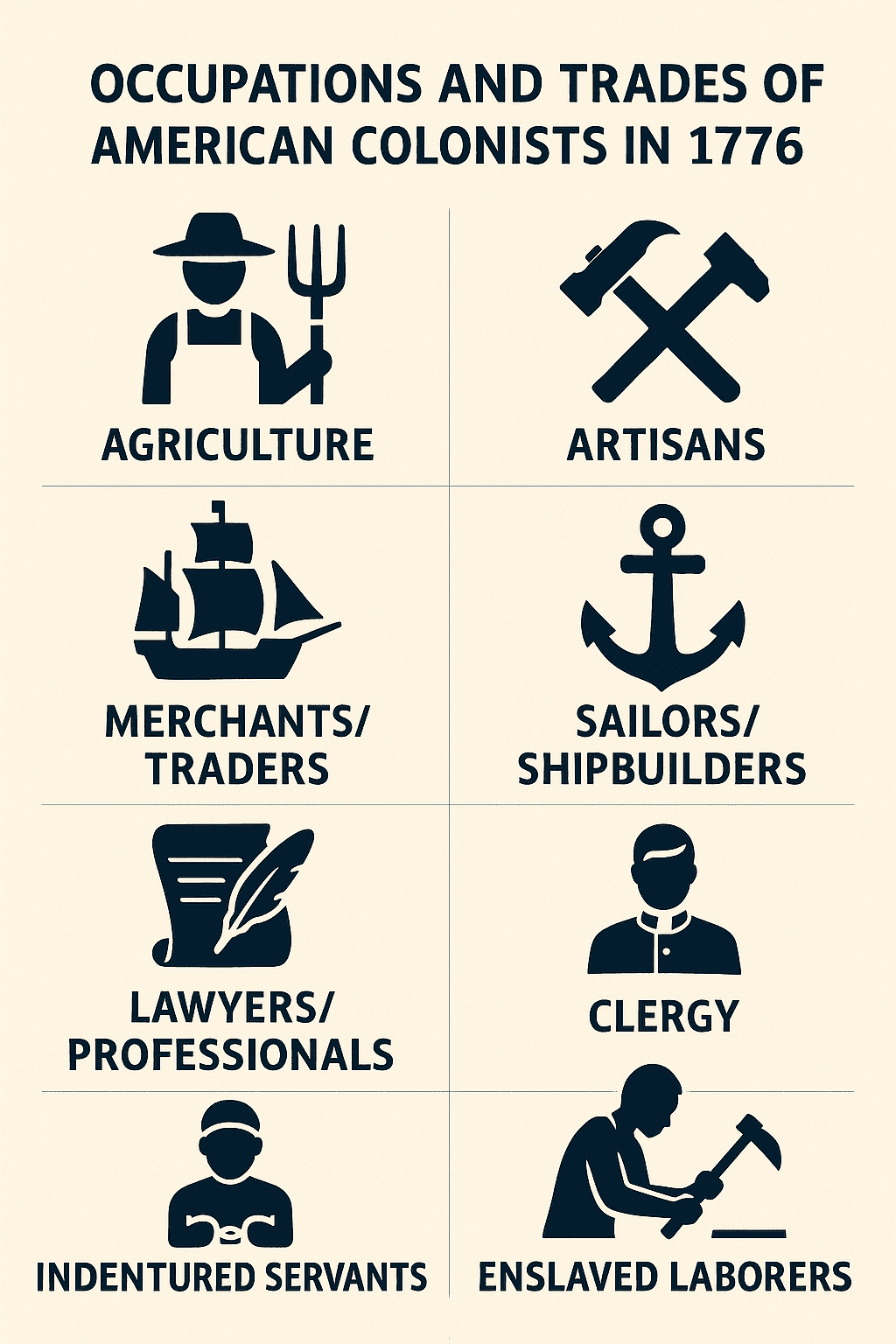

🛠️ Occupations and Trades in 1776: How Early Americans Made a Living

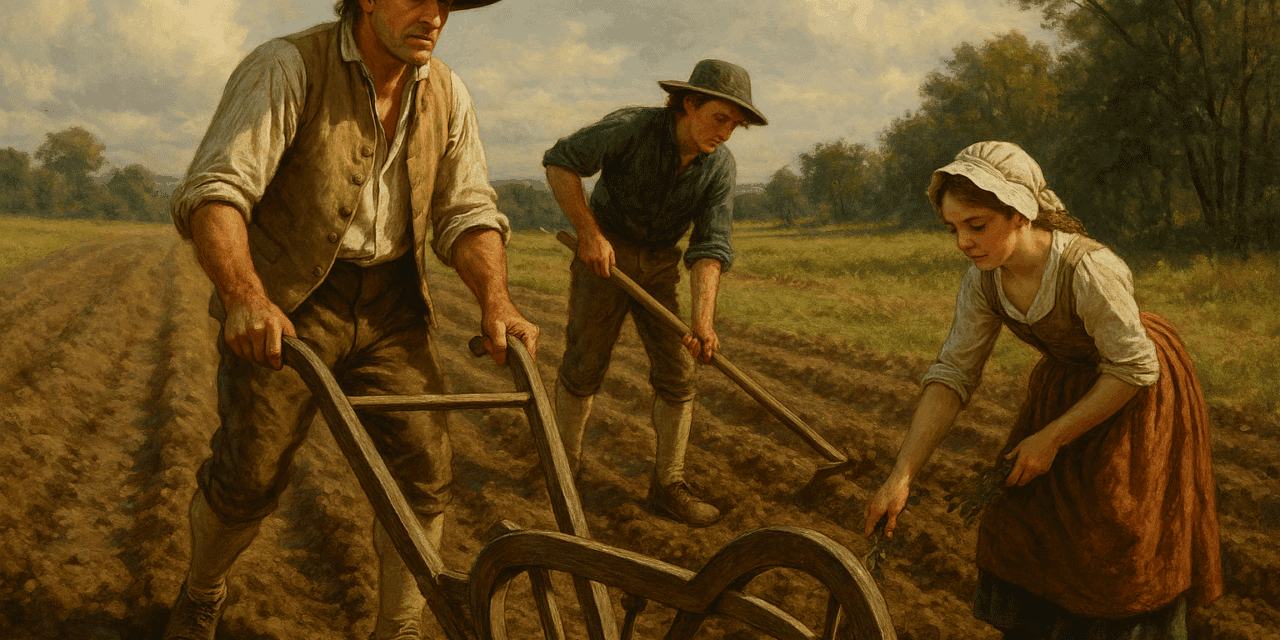

In 1776, colonial Americans were defined by the work they did, not just for wages, but for survival. Nearly every household was part of the self-sufficient economy that shaped life before and during the American Revolution. From small farms and artisan workshops to bustling ports and remote frontier settlements, the people who would become Americans relied on manual skill, labor, and trade to build their lives.

According to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, tradespeople, farmers, and enslaved workers formed the backbone of colonial society.

🌾 The Agrarian Majority: Farming Was a Way of Life

By far, the most common occupation in 1776 was farming—over 90% of colonists worked the land in some capacity:

-

- In New England and the Appalachian frontier, most families ran subsistence farms, growing crops and raising animals primarily for their own use.

-

- In the Southern colonies, plantation agriculture flourished with crops like tobacco, rice, and indigo—made possible by enslaved African labor.

Farmers not only fed their families, but they also produced surplus goods for trade or barter, forming the heart of the colonial economy.

For more, explore colonial farming life via Mount Vernon’s historical resources, which detail how Washington’s plantation was run during this period.

🧰 Skilled Trades and Artisan Professions

The cities and towns of colonial America supported a growing class of skilled tradesmen. The need for blacksmiths, carpenters, and coopers was universal—tools, transportation, and shelter were all hand-built.

Common Trades in 1776:

| Occupation | Role in Society |

|---|---|

| Blacksmith | Forged tools, weapons, nails, and horseshoes |

| Carpenter | Built homes, wagons, and furniture |

| Cooper | Made barrels for food, gunpowder, and shipping goods |

| Shoemaker | Created durable footwear for all seasons |

| Tailor | Sewed and repaired garments for men, women, and children |

| Tanner | Processed hides into usable leather |

| Printer | Published newspapers, pamphlets, and political literature |

| Wheelwright | Constructed and repaired wagons and carts |

You can explore colonial trades in detail at Colonial Williamsburg’s trades directory, which features videos and articles about the daily work of 18th-century artisans.

🏪 Merchants, Professionals, and the Emerging Urban Economy

In coastal cities like Philadelphia, Boston, and Charleston, merchants and professionals helped shape a growing commercial class:

-

- Merchants imported goods from Europe and exported raw materials such as lumber and cotton.

-

- Shopkeepers ran general stores supplying tools, textiles, and foodstuffs.

-

- Professionals included lawyers, doctors, ministers, and land surveyors, often educated at institutions like Harvard or William & Mary.

For more on urban life and commerce, see The American Revolution Institute’s economic overview.

⛓️ Enslaved and Indentured Labor: The Hidden Workforce

Not all labor in the colonies was voluntary:

-

- Enslaved Africans made up about 20% of the colonial population, mostly in the South. They worked not only in fields, but also as blacksmiths, carpenters, cooks, and domestic servants.

-

- Indentured servants, often poor Europeans, agreed to work 4–7 years to pay off their passage to America. They filled roles in both agriculture and skilled trades.

For in-depth records and personal stories of enslaved laborers, visit the Digital Public Library of America’s slavery archive.

🧶 The Work of Women: Mostly Unpaid, Always Essential

Though few women held formal occupations, their work was vital to survival:

-

- Women managed households, raised children, cooked, preserved food, and made candles, clothing, and soap.

-

- In some towns, widows or unmarried women operated boarding houses, bakeries, or ran family taverns.

-

- A few rare individuals became midwives, healers, or printers, like Mary Katherine Goddard, who printed the first copy of the Declaration of Independence with signer names.

The National Women’s History Museum explores the roles of colonial women and their often-overlooked contributions.

🌍 People at the Edges of Colonial Society

Many stories from 1776 focus on famous Founding Fathers and major battles, but much of American history was shaped by people who received little attention in early textbooks. Indigenous peoples, African Americans, enslaved people, and poorer white settlers along the Appalachian Mountains all experienced the Revolutionary War in different ways.

Indigenous nations and native people across North America found themselves caught between rival empires. Leaders such as Joseph Brant of the Mohawk and other Indian nations weighed alliances with either the British crown or the United Colonies, hoping to preserve their homelands.

Some sided with British troops, believing that victory for the British Empire might slow colonial expansion beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Others tried to stay neutral, knowing that whichever side won, Native Americans and indigenous peoples would continue to face pressure on their lands.

For people of African descent, the conflict was tangled up with the transatlantic slave trade and the daily reality of bondage. In port cities such as Boston, New York City, Charleston, and Newport, the economy was tightly connected to enslaved labor in the Caribbean and the southern colonies.

The first blood of the Revolution was shed by a man of African and Native descent, Crispus Attucks, killed in the Boston Massacre. During the war, thousands of African Americans served in colonial units and later in the Continental Army, while others escaped to the British army when promised freedom.

On the coast and in backcountry regions of New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Carolina, and South Carolina, local groups formed committees of safety, colonial militia units, and partisan bands. Figures like Ethan Allen in the north and other lesser-known military leaders in the south organized raids, seized forts, and held together fragile communities along the frontier. I

In places like Nova Scotia and Canada, other colonists chose loyalty to the British government, creating a different strand of colonial society.

The war also produced its share of complicated characters. Benedict Arnold began as a celebrated patriot and daring commander, but later joined British forces, becoming a symbol of betrayal in the nation’s history.

On the other side, French nobleman Marquis de Lafayette crossed the Atlantic to fight as a volunteer with American troops, forging a friendship with George Washington that would influence the form of government and ideals embraced by the young republic.

💡 Conclusion: The Work That Built a Nation

The colonists of 1776 lived in a world without safety nets, powered by manual labor, trade, and cooperation. Their work—whether in fields, forges, or printing presses—laid the economic foundation of a nation still in the making. Every trade, every crop, every service was connected to survival and community.

Understanding these colonial occupations gives us a clearer view of what independence meant: not just freedom from Britain, but the freedom to build something new with their own hands.

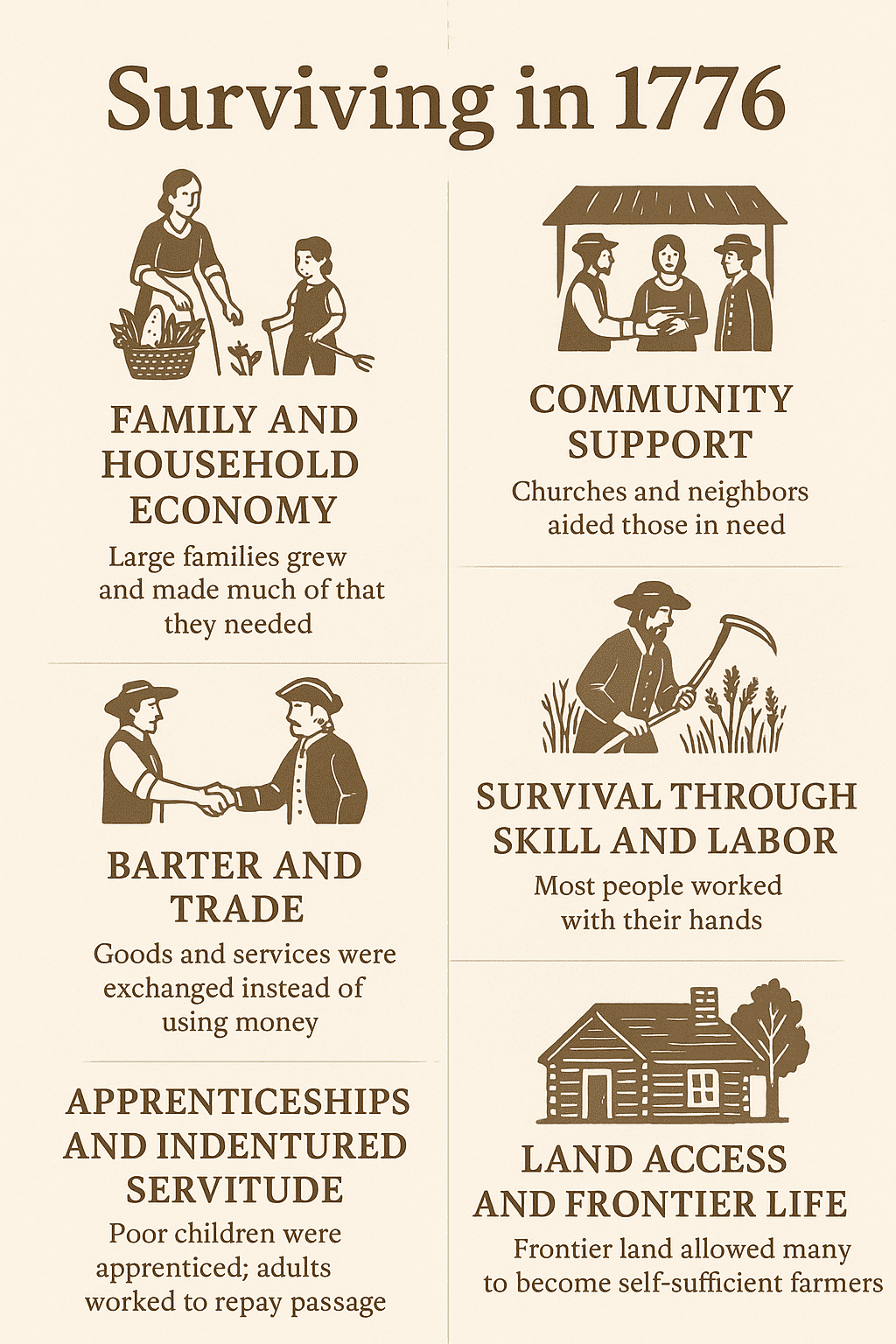

Without Government handouts in 1776, how did people survive?

There were no government handouts in 1776. No welfare programs, unemployment insurance, food stamps, or Social Security. Yet people found ways to survive, often through a mix of community support, self-sufficiency, family networks, and barter economies. Here’s how:

🔹 1. Family and Household Economy

-

- Large families were common, and everyone contributed—even children.

-

- Families grew their own food, made clothing, and did repairs.

-

- Women often maintained kitchen gardens, preserved food, and raised animals for meat, eggs, and dairy.

🔹 2. Barter and Trade

-

- Cash was scarce. Colonists often traded goods or services instead of using money.

-

- A barrel of corn might be exchanged for a blacksmith’s work.

-

- Midwives or healers might be paid with food, fabric, or labor.

-

- Cash was scarce. Colonists often traded goods or services instead of using money.

-

- Local economies relied on credit and trust, not formal banks.

🔹 3. Community Support

-

- Churches and neighbors helped those in need, especially widows, orphans, and the elderly.

-

- Barn raisings, harvest help, and communal building projects were common.

-

- Religious groups like the Quakers and Congregationalists took responsibility for poor members.

🔹 4. Apprenticeships and Indentured Servitude

-

- Poor children might be sent to apprentice with craftsmen in exchange for food, shelter, and training.

-

- Adults who couldn’t afford passage to America became indentured servants, working for 4–7 years to repay the cost.

🔹 5. Survival Through Skill and Labor

-

- Most people worked with their hands and had multiple skills: farming, carpentry, spinning, and animal care.

-

- People lived close to the land and often in extended family units that shared labor and resources.

🔹 6. Land Access and Frontier Life

-

- Land was more available (especially on the frontier), allowing many to become self-sufficient farmers.

-

- Though frontier life was harsh, it gave the poor a chance to own property and produce their own food.

⚠️ No Safety Net — But Also Lower Expectations

-

- There was no expectation that the government would provide assistance.

-

- People relied on each other, and survival skills were essential from an early age.

-

- Poverty existed, but it looked different, closer to subsistence living rather than homelessness or urban destitution as seen later.

Were people living in the 13 colonies considered British citizens?

✅ British Subject Status Before July 4, 1776

-

- Anyone born in the colonies was legally a British subject, with rights and obligations under British law.

-

- Immigrants from other countries (like Germany or the Netherlands) who naturalized under colonial or British law also became British subjects.

-

- British subjectship could also be granted automatically to immigrants after meeting certain residence requirements in some colonies, especially under acts like the Naturalization Act of 1740.

-

- The Naturalization Act of 1740 allowed Protestants (excluding Catholics and Jews) who had lived in the colonies for 7 years and taken an oath of allegiance to the Crown to be considered natural-born subjects.

When we picture the Revolutionary War, we usually think of battle lines and famous founders. But women were there too—organizing supplies, nursing the wounded, keeping families afloat, carrying water under fire, and in rare cases even stepping into combat roles. Their work was essential, and their stories belong in any complete account of American independence.

⚖️ Exceptions and Special Cases

-

- Enslaved Africans were not considered citizens or subjects with rights—they were legal property under colonial law.

-

- Native Americans were not British subjects unless they explicitly pledged allegiance or assimilated under colonial authority (rare).

-

- French, Spanish, or Dutch settlers in newly acquired territories (like Florida or Quebec) were in a gray area until they accepted British rule or relocated.

🔄 After July 4, 1776

-

- The status of being a British subject ended for those who pledged allegiance to the United States—but only in principle. Britain still considered the colonists as rebels and did not recognize their independence until the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

-

- Some colonists—especially Loyalists—remained loyal British subjects and eventually fled to Canada, the Caribbean, or England after the war.

🗽 Did Colonists Automatically Become American Citizens After 1776?

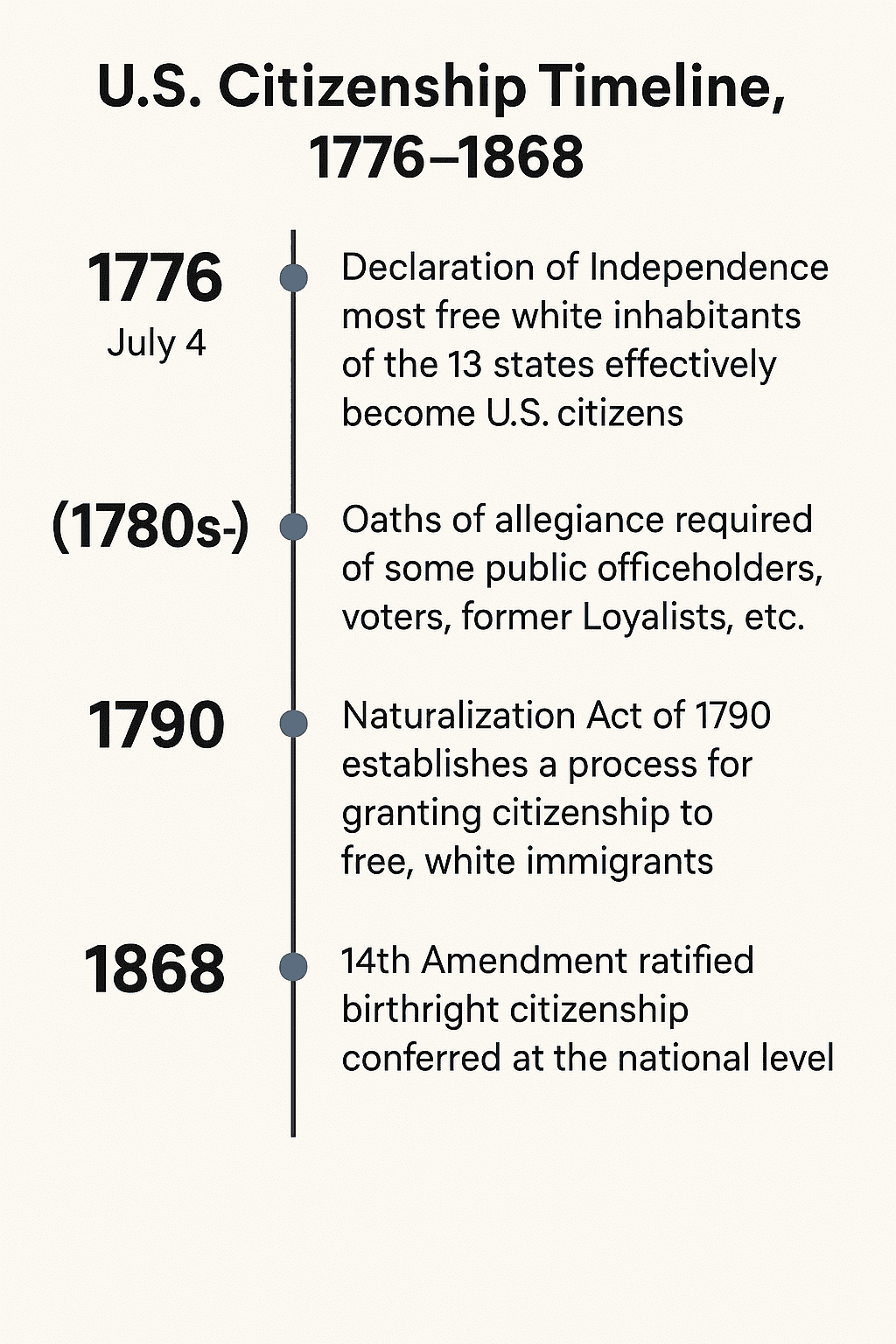

When the American colonies declared independence from Britain in 1776, the question of who was an American citizen wasn’t clearly defined. Unlike today, there was no formal citizenship process at the national level. Most free white colonists were simply considered citizens by default, but this shift from British subject to American citizen was neither automatic nor inclusive for everyone.

According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) historical overview, “the concept of U.S. citizenship evolved gradually,” especially before the 14th Amendment defined it in 1868.

👉 USCIS History of U.S. Citizenship

⚖️ Citizenship After the Declaration of Independence

-

- After July 4, 1776, colonists no longer held allegiance to the British Crown. Most free white male residents of the 13 colonies became state citizens, and this implied national citizenship, though there was no formal federal designation yet.

-

- Each state governed its own citizenship laws, voting rights, and property ownership criteria.

-

- The Articles of Confederation (1781) and later the U.S. Constitution (1788) used the term “citizens of the United States” but offered no legal definition.

👉 Source: National Archives – The U.S. Constitution

🖋️ Were Loyalty Oaths Required?

Yes—in many states, loyalty oaths were required, particularly between 1776 and 1783.

-

- Oaths of Allegiance renounced loyalty to King George III and pledged support to the state or the United States.

-

- These oaths were required to:

-

- Vote

-

- Serve in militias

-

- Hold public office

-

- Own property in some jurisdictions

-

- These oaths were required to:

For example, in Pennsylvania, residents had to sign an oath beginning in 1777 or risk being labeled a Loyalist (Tory) and stripped of rights.

👉 Pennsylvania State Archives – Oaths of Allegiance

❌ Who Was Not Considered a Citizen?

The early understanding of U.S. citizenship was exclusive, not inclusive.

| Group | Status in Post-1776 America |

|---|---|

| Enslaved Africans | Considered property; had no legal personhood or citizenship rights |

| Free Black Individuals | Varying status by state; few civil rights and mostly denied national recognition |

| Women | Considered part of citizen households but denied voting and legal independence |

| Native Americans | Not considered U.S. citizens; belonged to separate sovereign nations |

| Loyalists | Often stripped of property, rights, and even forced to flee to Canada or Britain |

| Recent Immigrants | Had to meet state-level requirements and often take a loyalty oath |

👉 More context: National Constitution Center – What Is Citizenship?

📜 Citizenship After the Constitution Was Ratified (1788)

The U.S. Constitution referenced “citizens of the United States” (e.g., in Article I and IV), but did not define who qualified. That responsibility was still left to the states.

The first formal national citizenship policy came with the Naturalization Act of 1790, which allowed:

-

- Free white males who had resided in the U.S. for 2 years

-

- Of “good moral character.”

-

- To apply for naturalized citizenship

This excluded women, enslaved people, Native Americans, and non-white immigrants.

👉 Full text: Library of Congress – Naturalization Act of 1790

🧠 When Was Citizenship Officially Defined?

The clearest definition of national citizenship came with the 14th Amendment (1868):

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

👉 National Archives – 14th Amendment

This marked a turning point—especially for formerly enslaved individuals and other marginalized groups—finally enshrining a broader, inclusive definition of American citizenship.

🧭 Summary: From Subjects to Citizens

-

- Most free white colonists became citizens by assumption and allegiance after 1776.

-

- Loyalty oaths formalized their break from Britain in many states.

-

- Citizenship was selective, shaped by race, gender, and class, until later reforms expanded the definition.

-

- The journey from British subjects to American citizens was not just legal—it was transformational, and it laid the foundation for how we define what it means to be an American today.

📚 Enduring Ideas: Rights, Citizenship, and America’s Future

When Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence, he drew on English traditions like the Magna Carta as well as colonial experience. The famous reference to unalienable rights—sometimes spelled inalienable rights—gave voice to a belief that basic individual rights and equal rights did not come from a king or from Parliament.

They were gifts from the Creator and belonged to all people by nature. The Library of Congress preserves Jefferson’s early drafts, which show how carefully the delegates of the Second Continental Congress chose every word.

In practice, these enduring principles of the Declaration of Independence were applied only to a narrow slice of society in 1776: mostly free white men who owned property. Yet the language of the document traveled far beyond that original audience.

Over the next century, leaders and activists would keep returning to those promises. Abraham Lincoln quoted the Declaration to argue against slavery and to defend the United States Constitution. Generations later, civil rights movements would invoke those same phrases to push the nation closer to genuine equal rights.

The early debates over citizenship, loyalty oaths, and the responsibilities of states helped shape the eventual Bill of Rights and later amendments. Thinkers like James Madison and Alexander Hamilton worried about how to balance liberty and order in a new form of government.

The Constitution they framed, and the amendments that followed, tried to correct some of the injustices built into colonial society, even though change came slowly and often only after conflict.

Many of the men we remember from this era—George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Paul Revere, John Paul Jones, and later presidents like Andrew Jackson—were not just military leaders or politicians. They were also symbols of what the new nation might become.

At the same time, lesser-known figures such as Patrick Henry, with his “liberty or death” speech, and countless unnamed soldiers in the Continental Army and colonial militia, carried the risks of rebellion on their shoulders.

By the following year after independence, people in places like New York City, New Jersey, North Carolina, and South Carolina were already debating what citizenship should mean in everyday life. Who could vote? Who could hold office? How much power should the new federal government have over the states?

These questions would eventually lead to new compromises, new conflicts, and, decades later, to another brutal test of unity in the Civil War.

📣 Stay Connected to the USA250 Series

Return to RetireCoast.com each month for a new article in our ongoing USA 250th Anniversary Series, continuing through July 2026. Our mission is to bring you fascinating stories and overlooked facts about one of the most important events in human history—the birth of the United States.

We promise content you likely haven’t read in textbooks or seen in documentaries.

💬 Leave us a comment, and don’t forget to subscribe using the email sign-up box at the top right of this page so you’ll never miss a new post. Check out this article.

🔍 To find all related content, simply search our site for “USA250”.

👇 Click the link below to read our cornerstone article:

FAQ

Frequently Asked Questions About Life in 1776

1. Who was the average colonist in 1776?

The average colonist was a young person—under 20 years old—likely born in the colonies to English or German-speaking parents. They lived in a rural area, worked on a family farm, and practiced Protestant Christianity. Education was minimal, especially outside New England, and daily life was shaped by self-reliance, faith, and community.

2. What percentage of colonists were farmers?

Approximately 90% of colonists worked in agriculture, either as independent farmers, sharecroppers, or laborers on plantations.

3. Did colonists live longer or shorter lives than we do today?

Life expectancy at birth was around 35–45 years, but many who survived childhood lived into their 60s or beyond. High infant mortality lowered the average.

4. What religions were practiced in the colonies?

Most colonists were Protestant Christians, including Anglicans, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Baptists, Quakers, and Lutherans. Minorities included Catholics, Jews, and adherents to African and Native American spiritual traditions.

5. How educated were colonists?

Literacy was high in New England among white males (up to 90%) but lower in the South and frontier. Most education came from home or church schools. Slaves and women had limited access to formal education.

6. Did colonists become American citizens automatically?

Most free white colonists were considered citizens by default after independence, especially if they took loyalty oaths. Citizenship wasn’t formally defined until the 14th Amendment in 1868.

7. Were all people in the colonies free?

No. About 20% of the population were enslaved Africans. Some Native Americans were held in bondage or displaced. Indentured servants also had limited rights until their service ended.

8. What languages were spoken in the colonies?

English was dominant, but German, Dutch, French, Gaelic, and African languages were also spoken. Many enslaved people developed Creole dialects like Gullah.

9. How did colonists survive without government aid?

Families relied on self-sufficiency, barter, apprenticeships, and community help. Churches and neighbors played a key role in caring for the sick or poor.

10. What kind of work did children do?

Children helped with farming, cooking, cleaning, and crafts from a young age. Boys might apprentice by age 12; girls often learned domestic skills early.

11. Did women work outside the home?

Most women managed the household and supported farm work. Some ran taverns, shops, or midwifery practices. Widows occasionally operated family businesses.

12. What role did Native Americans play in colonial life?

Native Americans were vital to trade, diplomacy, and conflict. Some allied with colonists; others resisted encroachment. Their spiritual practices remained strong despite missionary efforts.

13. How did people travel and communicate?

Most travel was by foot, horseback, or wagon. Communication was slow—letters and newspapers were the main sources of information, often taking weeks to arrive.

14. What foods did colonists eat?

Diets were seasonal and based on what could be grown or raised. Common foods included cornmeal, pork, beans, apples, and bread. Hunting and fishing were also common.

15. What did colonists do for fun?

Socializing at taverns, church events, dances, storytelling, and games were popular. Music, quilting bees, and militia musters served as community gatherings.

🇺🇸 Explore More in Our 250th Anniversary Series

This article is part of our ongoing RetireCoast historical series celebrating

America’s 250th Anniversary.

Visit the full hub page to explore more stories, research, and perspectives from 1776 to today.

PODCAST

Discover more from RetireCoast.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.